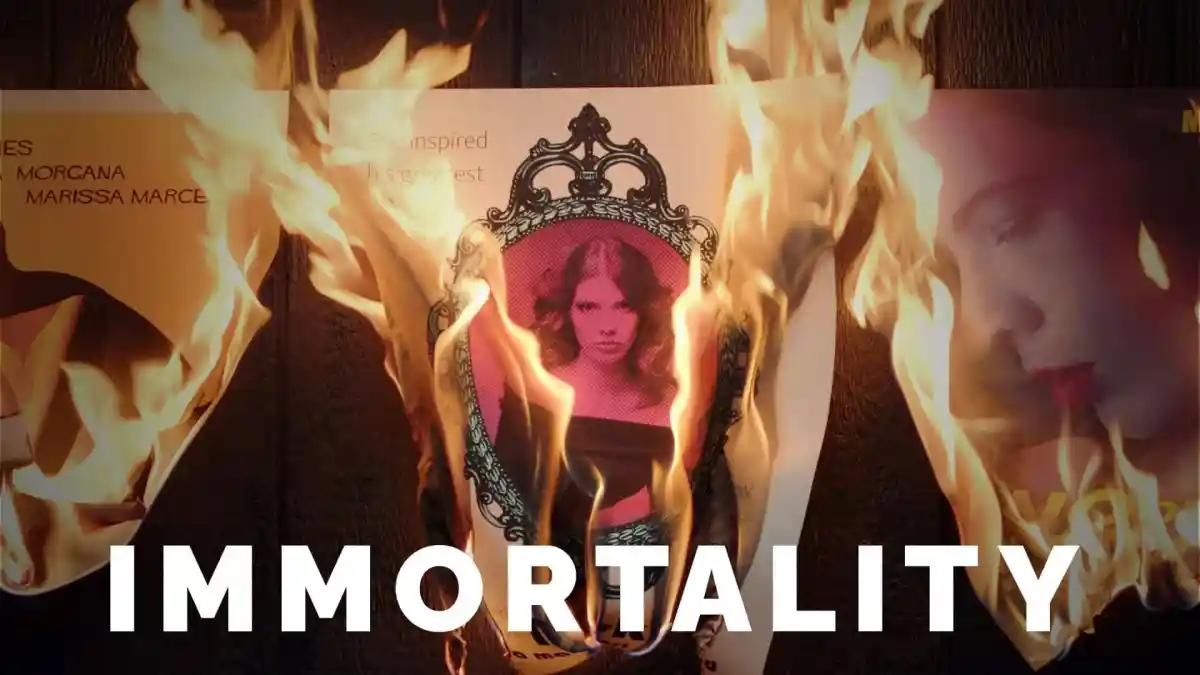

The premise and marketing of Immortality, the latest title from Sam Barlow and the team at Half Mermaid, put the mystery of Marissa Marcel front and center. Having rolled credits, I know what happened to her, but I’m not sure I fully understand it. That’s because Immortality isn’t really interested in the character of Marissa. Instead, like Her Story and Telling Lies before it, Immortality engages the player as a participant in the way the story unfolds. However, it differs from Barlow’s earlier games by stripping away the fourth wall, casting you as yourself, and thus challenging you to understand it entirely on your own terms.

Immortality sets you to sifting through archival footage from three unreleased films. It’s structurally similar to Barlow’s earlier FMV-style games, except that those had you participating as a character relevant to the story. Not so here. Immortality is more like Doki Doki Literature Club; it insists that everything you see is real. You become the heart of the experience and the locus of meaning in a way most games only claim to.

That’s not to say Immortality is without authorial intent. It feels scatterbrained because of the almost random way you move through footage, but it comes together through glimpses. Footage from in-universe film Minksy in concert with table reads alludes to the perils and difficulties of making art. The story of Two of Everything alongside crew interviews and other behind-the-scenes footage explores duality and the struggles associated with celebrity.

And then, of course, there’s the theme of “immortality.” Like so much else in the game, the title operates on multiple levels. At its most obvious, it’s a reference to the idea that film is a form of immortality, that performances or lives captured on camera can exist forever. On a deep narrative level, it references the literal concept of immortality (but to elaborate would get into spoilers). For me, the most intriguing interpretation of the title is the idea of literary immortality.

The idea is ancient, but it has developed over time. Plato’s Republic suggests using stories to educate future generations, passing on relevant and worthwhile tales to guide people to become good citizens — with the implication that these stories live into the distant future through the curriculum of the ideal state. Shakespeare was more direct in his “Sonnet 55”: “Not marble nor the gilded monuments / Of princes shall outlive this powerful rhyme.” And later, Percy Bysshe Shelley would offer a subversive take on the same concept with the epigraph described in “Ozymandias”: “Look on my Works, Ye Mighty, and despair!”

Words and stories persist because they exist in the minds of their readers, viewers, or players. And, as “Ozymandias” suggests, those words and stories can mean very different things depending on the perspective with which they are received. This assertion leads directly to the rise of reader-response criticism in the 1960s and everyone’s favorite Literature 101 reference, Roland Barthes’ “The Death of the Author.” Barthes argues that “In the multiplicity of writing, everything is to be disentangled, nothing deciphered,” which perfectly encapsulates the sensations of playing Immortality. The game is less interested in having you solve the mystery than in having you work through the process.

That doesn’t mean the solution is meaningless, because the ending, like those of Barlow’s other works, reconfigures your understanding of the experience. Again, it centers you.

The endlessly recursive, reader-centered nature of stories is a fixture of the game. At first, it appears only loosely. The first of Marissa’s films, Ambrosio, is an adaptation of a much earlier Gothic novel, and adaptation is narrative filtered through both a new form and the interpretation of the individual(s) responsible for the adaptation. Then hidden in the archives for Minksy is the explicit question of what audiences will think of the film’s director playing the title role. Two of Everything feels, in many ways, like the trilogy turning back on itself to inspect the processes of the earlier films in view of the years between.

I came to these interpretations, these apparent internal links, because of the way I explored the game’s possibilities. Immortality defies any attempt to impose linearity. Randomness is a pillar of its design. No two players will have the same experience, which means the patterns and themes that emerge will be both subjectively and objectively different. That’s where the game becomes an expression of “The Death of the Author” — “there is one place where this multiplicity is focused and that place is the reader.”

You might enjoy a more direct path than mine to the answer of what happened to each film and what happened to Marissa. Or you might find a cleaner trail of breadcrumbs that makes the ending more immediately clear. Whatever path you take, you will eventually arrive at the same endpoint. The mystery is solved, and then there’s something lurking beyond the footage. As I’ve been saying all along, that end is less about Marissa than it is about you.

There’s a good chance you will interpret it differently; your path through the game, your fundamental understandings of its multifarious pieces will be different from mine because our experiences differ. For me, it crystallized the sense that what Barlow and Half Mermaid explicitly explored though the multiplicities of Immortality matters far, far less than what I took from the experience. Is that, in fact, the point?

Maybe. Maybe not. But if it is, it leaves just one thing to do: to distill my experience.

There’s all manner of takes that can be pulled out, from the challenges of working with toxic people to the cavalier cruelty of classism. There are statements about sexism, creative freedom, loneliness, and the lengths to which people will go for just a small taste of what they really want.

What stood out to me, however, was failed ambition. The entire game is premised upon it. Marissa could have been a star, but it was not to be her path. Each of her three films failed to come together, and so suffered those around her. No one really succeeds. But it extends beyond the story to the game’s construction.

I hesitate to call Immortality a failure because it succeeds in being a thoughtful, challenging experience, yet there is something Icarian about it. It wants for clarity. There’s a sense of too many moving parts. The ambition outstrips the execution, and ultimately, the lack of cohesion in the storytelling and the way the energy can grind to a halt with no warning because of the inherent randomness leaves an oddly dissatisfying note.

Published: Sep 14, 2022 11:00 am