The appeal of Michael Myers is both exceeding simple and easy to overcomplicate.

Halloween’s Myers has endured for over four decades, becoming a horror icon in his own right. Versions of the character have appeared in 11 films across various iterations of the franchise, played by 13 different actors. With his white mask, boiler suit, and kitchen knife, Michael Myers is genuinely iconic. Why is Myers so effective? What makes this particular monster so compelling? And given the character’s seeming simplicity, why have so many films struggled to capture what makes Myers so haunting?

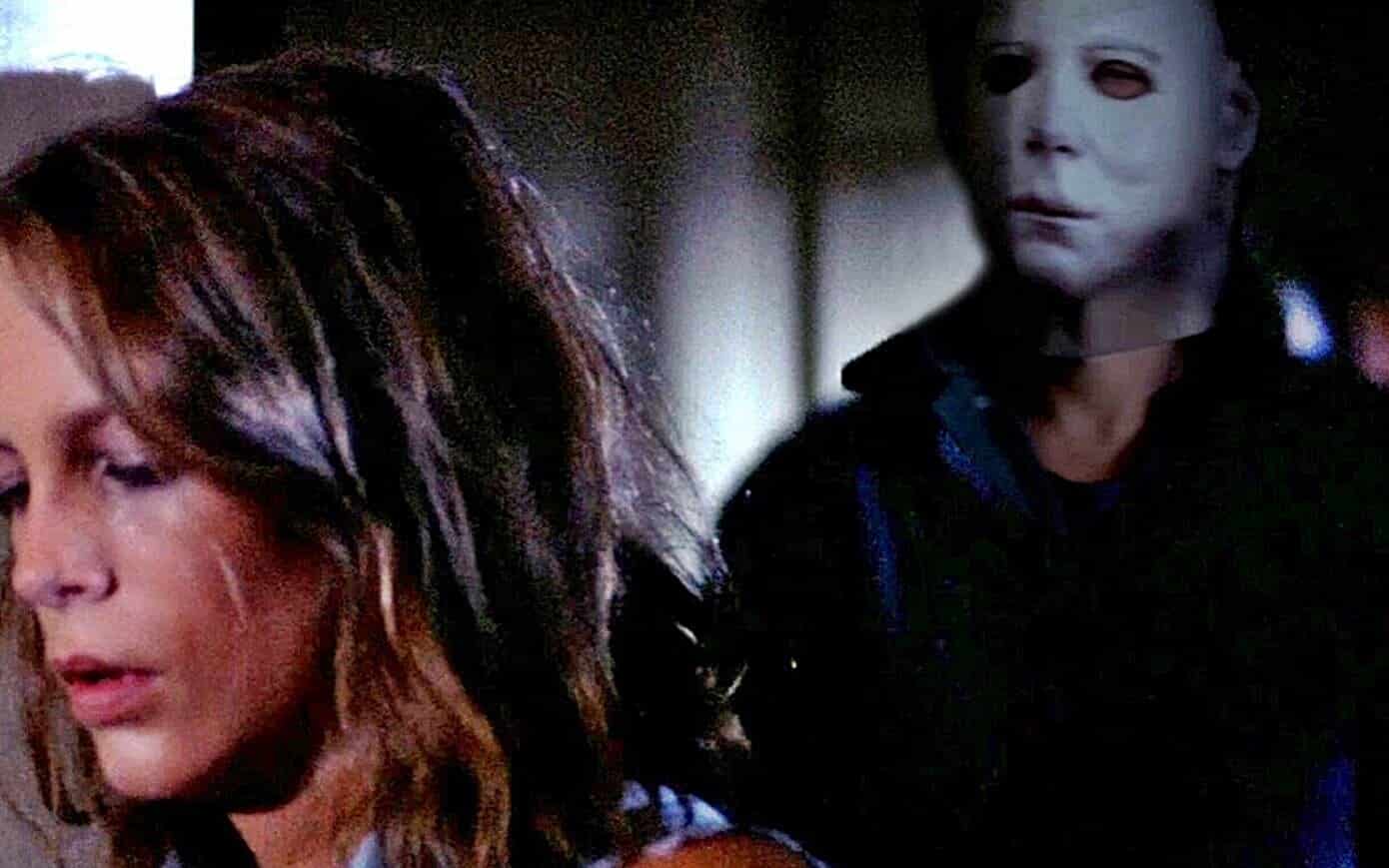

The most obvious identifying aspect of Michael Myers is the character’s mask, which was famously a William Shatner mask painted white. It’s a simple and haunting visual — what Oscar-winning FX and makeup artist Chris Nelson would describe as “the perfect storm” that the franchise would spend decades trying to replicate. The mask is uncanny. It looks almost human but is just alien enough to become unsettling. There is an unnerving blankness to Michael Myers.

The character’s silence is striking, particularly in contrast to other comparable slasher movie antagonists. Billy in Black Christmas cannot resist making lewd phone calls. Freddy Krueger from A Nightmare on Elm Street is basically a prop comedian. Ghostface from Scream takes sadistic pleasure in taunting his prey. Even Leatherface from The Texas Chainsaw Massacre is frequently wailing and grunting. In contrast, Myers is defined largely by his stillness and his silence.

Writer and director John Carpenter has talked about Myers as “a force of nature,” explaining, “He’s a guy that has no personality, no character.” Carpenter has even cited “the robot gunfighter” (Yul Brynner) in Westworld as a major influence on the serial killer. In some ways, Myers feels like a singular anthropomorphic personification of the various faceless hordes in many of Carpenter’s other movies: the gang in Assault on Precinct 13, the alien in The Thing, the crowd in Prince of Darkness.

Psychiatrist Sam Loomis (Donald Pleasence) spends most of the original Halloween franchise insisting that Myers is “purely and simply evil.” As he drives up to Smith’s Grove Sanitarium, Loomis warns his colleague Marion Chambers (Nancy Stephens), “Don’t underestimate it.” Marion responds by asking, “Don’t you think we could refer to it as him?” Loomis only grudgingly obliges, “If you say so.” The closing credits seem to side with Loomis, referring to Myers as “the Shape.”

It’s worth putting Myers in context. Halloween was released during the late 1970s, as America was increasingly fixated on sensationalist reporting of horrifically violent crime, particularly serial killers. The 1960s had come to an end with the Manson Family murders and the Zodiac Killer terrorizing the nation — traumas that seemed to have no rational explanation. During the 1970s, serial killers like Son of Sam and Ted Bundy garnered national media attention.

The art of profiling and explaining these sorts of offenders only really came to national attention in the decades that followed. John E. Douglas arrived in Georgia in 1981 to help solve the Atlanta Child Murders. His profile garnered press coverage later in the decade, following the arrest of Wayne Williams. Douglas inspired the character of Jack Crawford in Thomas Harris’ Red Dragon, published in 1981. While far from the first novel looking at serial killers, Red Dragon reinvented the genre.

All this is to emphasize that Michael Myers was a character who manifested at an interesting time in America’s relationship with serial killers. Myers was undoubtedly a recognizable archetype who reflected public fascination with this sort of violence, but he arrived just before pop culture really embraced a language to explore and understand the pathology driving these crimes. Myers arrived at one of the last moments when these sorts of criminals were truly inexplicable.

However, there is something even more unsettling about the way that Carpenter approaches Michael Myers in Halloween. Notably, the film opens with an extended tracking shot from Myers’ perspective. The camera is put inside Myers’ head as he commits his first murder. The audience is asked to witness the crime through Myers’ eyes. Later on, as Myers stalks his future victims, the camera is often placed so the audience is never sure if they are watching from Myers’ perspective.

Of course, voyeurism is nothing new. Cinema is inherently voyeuristic. This is particularly true of horror, which is largely built around the tension of the audience’s desire to watch horrible things happen to characters on screen. After all, these movies wouldn’t exist if audiences didn’t want to see them. Halloween is built around that anxiety. Michael Myers wears a mask, because that might be all that he is. Underneath that mask, he is just a vehicle for the audience’s voyeuristic tendencies.

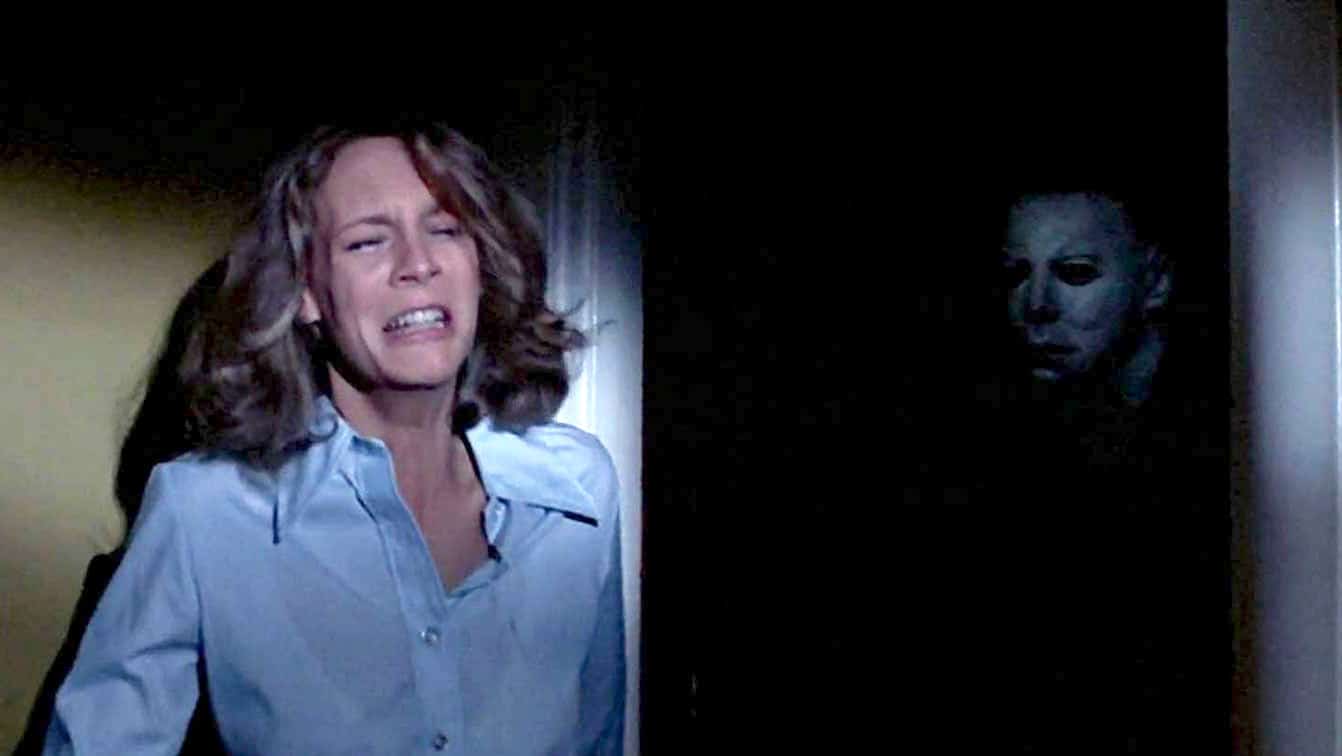

This theme of voyeurism is woven into the script of Halloween. At one point, Laurie Strode (Jamie Lee Curtis) complains that a neighbor was watching her. Her friend Annie Brackett (Nancy Kyes) protests that the neighbor in question is elderly. “He can still watch,” Laurie insists. “That’s probably all he can do,” Annie replies. This is in the context of a horror movie being watched by an audience, which repeatedly draws attention to its characters watching horror movies on television.

Much has been made of the sexual politics of Halloween, particularly the argument that Laurie survives because (unlike her friends) she doesn’t have sex. However, there’s more to it than that. It is true that Laurie does not have sex in Halloween. Instead, the film draws attention to her own voyeuristic impulses. Her friends are surprised when she asks what they are going to wear to the Halloween dance. “I didn’t know you thought about things like that, Laurie,” Annie replies.

Clearly, Laurie thinks about that stuff a lot; she just doesn’t act on it. She admits that she thinks about specific boys, even if she would never do anything to realize that desire. Halloween positions Myers in a space between Laurie and the audience. Just as Laurie fantasizes about the sorts of illicit encounters that her friends enjoy, Halloween wonders whether some part of its audience enjoys the thrill of seeing this violence through Myers’ eyes. That vacant mask isn’t a mirror, but a window.

Carpenter would return as the writer for Halloween II. He also took creative control of the film when he was unsatisfied with director Rick Rosenthal’s work, explaining, “We did a little recutting, and then we did some reshooting.” Carpenter would later candidly describe it as “an abomination and a horrible movie.” However, some of the film does underscore these themes. One of the film’s early effective sequences puts the audience right back in Myers’ head.

Halloween II also positions Myers as much more of an archetypal movie monster. Early on, Myers lumbers around as the television plays Night of the Living Dead. Later on, he appears on grainy CCTV footage like some B-movie fiend. Myers’ kills more directly invoke classic horror cinema; he holds a nurse’s head under boiling water in a sequence that recalls a memorable moment from James Whale’s Frankenstein and sucks another’s blood out like a modern-day Dracula.

This was also the point where the franchise starts explaining Michael Myers. When NBC wanted to air Halloween, they asked Carpenter for eight minutes of new material to fill out the broadcast block. “So I had to come up with something,” Carpenter explains. “I think it was, perhaps, a late night fueled by alcoholic beverages, was that idea. A terrible, stupid idea!” Some of that new material, folded into Halloween II, was the “awful, just awful” reveal that Myers was Laurie’s brother.

This immediately robs the character of a lot of his mystery and menace. As Danny McBride, who co-wrote the requel Halloween, argued, “It seemed too personalized.” In the original movie, the fear was that Michael Myers could be anywhere. “You know, every town has something like this,” a graveyard groundskeeper (Arthur Malet) tells Loomis. From Halloween II onwards, Myers becomes much more specific. The series begins to fill in the finer details of the Shape.

Halloween IV: The Return of Michael Myers doubles down on the religious metaphor, consigning Myers to “hell” and casting Loomis as a “pilgrim.” Halloween V: The Revenge of Michael Myers starts adding weird runes and hints of a larger conspiracy to the character, perhaps tied to the contemporaneous satanic panic. Halloween VI: The Curse of Michael Myers seeks to explain Michael by citing “ancient druids” and “blood sacrifices.” Rob Zombie’s 2007 reboot promises “evil has a destiny.”

On paper, Rick Rosenthal’s return to the franchise in Halloween: Resurrection seems to mock these efforts to account for Michael Myers. It follows a group of teenagers challenged to spend the night in Myers’ childhood house for a reality web series. They encounter all sorts of props hinting at Myers’ traumatic past, only to discover those props were planted by unscrupulous producer Freddie Harris (Busta Rhymes) to create cheap drama.

Resurrection returns to the language of the original. There are many shots from Myers’ perspective. The streaming plot hook emphasizes the voyeuristic nature of the slasher. However, Resurrection is simply terrible. It is retroactive vindication of Carpenter’s decision to reshoot large portions of Rosenthal’s Halloween II. It also features the most 2002 moment ever: Busta Rhymes shouting “trick or treat, motherfucker” while roundhouse kicking Myers and then electrocuting him in the genitals.

As such, it makes sense that David Gordon Green’s Halloween (2018) stripped all of that back, explicitly and aggressively rolling the franchise back to the original film and erasing all of the storied continuity including Myers’ relationship to Laurie. The best sequence in the film is a long take of Myers murdering his way down a crowded suburban street, with no reason or motivation for the carnage he causes. Myers is once again a shape in the night, a boogeyman in the dark.

Published: Oct 18, 2021 11:00 am