Terra Nil is a reaction. It’s a response to the glacial pace with which global leaders are moving to mitigate the climate crisis. The game’s far-future world is one where any attempts to course-correct were too little, too late. For all that, it doesn’t wallow in the misery of hopelessness. It doesn’t preach or proselytize; instead, it sets you the implausible task of restoring the environment. In that, Terra Nil is an expression of hope, yet there’s still a darkness lurking beneath its utopian surface.

I previewed this “reverse city builder” a couple of years ago, and the final version extends on everything I thought then. It’s an eminently soothing experience that radically reimagines genre norms.

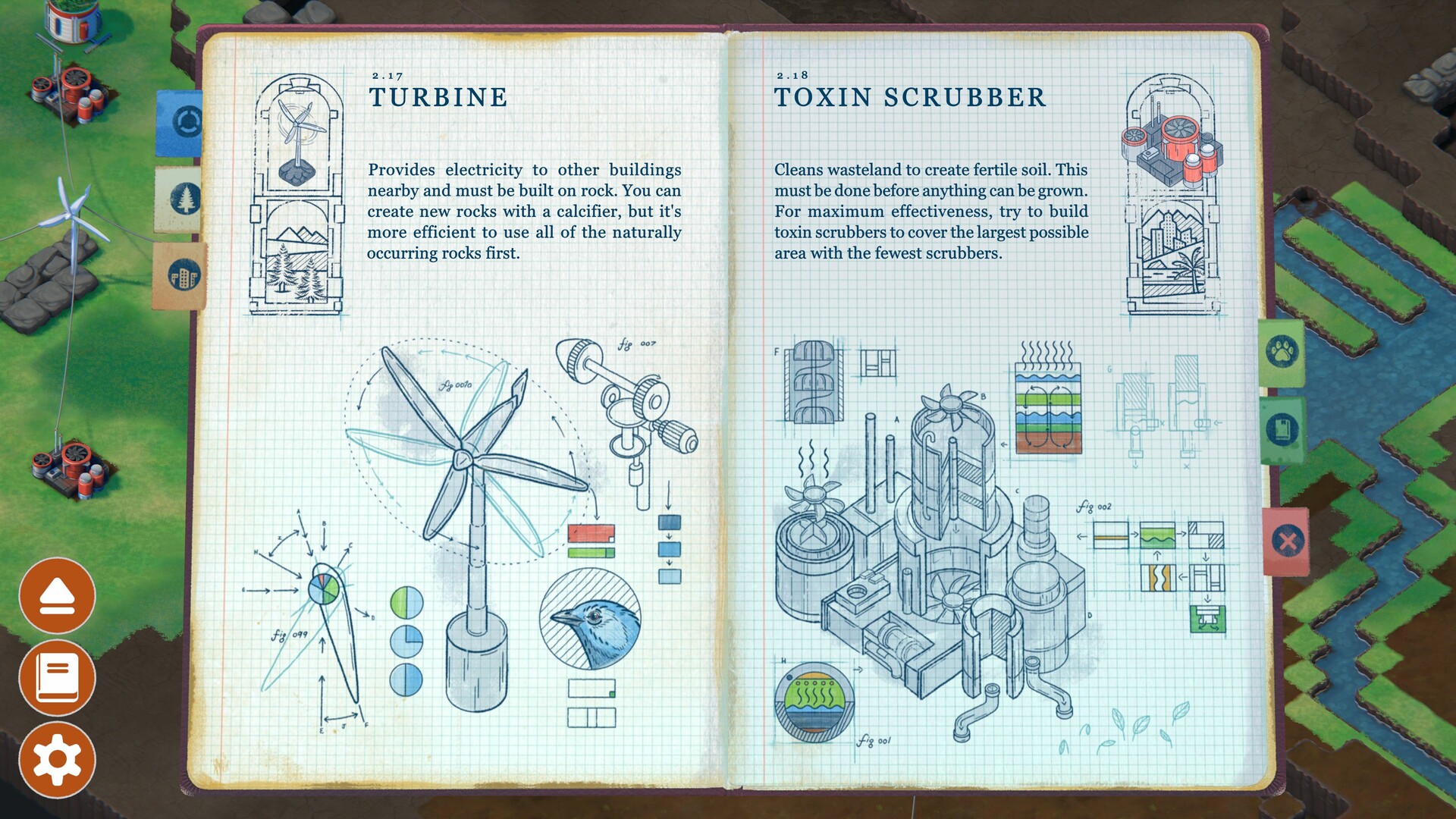

Usually, you’re responding to the needs of a growing population — dealing with electricity, water, and sewage in SimCity or Cities: Skylines or hunger and social discontent in Frostpunk. In Terra Nil, you’re balancing ecology rather than economy: wind turbines produce energy for toxin scrubbers that allow irrigators to fertilize the once-barren soil. The dizzying array of speculative fiction tools enables the growth of grasslands, forests, wetlands, and plenty of other biomes besides. Humans never once factor into the equation.

The circularity of the ecological economy makes for a delightfully compelling gameplay loop, but that’s less of a draw than the hope that permeates the experience. It’s there in the gentle soundtrack and naturalistic audio effects, the bright visuals and the way color and life sweeps into each environment as you work. Most of all, though, it’s there in the freedom to make mistakes.

I remember restarting several times for my preview. Maybe it’s because of that muscle memory or maybe it’s because I played on Gardener mode (the easiest setting), but I never had to start over in the release version of Terra Nil. There’s an undeniable puzzle element to the game, but it’s one where you work towards an outcome rather than a solution.

To that end, if you have the wrong ecological balance, you can burn down forests to recreate it as savannah or blast channels for rivers and lakes. There is always space to recognize your errors and reset, recalibrate, and make amends. It stands in contrast to the almost militaristic discourse that surrounds real-world climate change, an all-or-nothing, take-it-or-leave-it demand that says action is needed now.

That’s one of the most optimistic things about the game. It suggests there’s always a way out. And in that respect, Terra Nil taps into the ideology of the hopepunk genre, even if the game doesn’t fully adhere to its parameters. The genre is generally seen as a response to the bleakness of the modern age — an age of war, increasing reportage of violent crime, economic instability, petty politics, and divisive rhetoric at all levels. Hopepunk recognizes these social features and argues that the way out is kindness and collective action. The stories often reflect a sense of bleakness, but they offer a deep breath and a slow exhale on the way dispelling that bleakness.

While its cathartic feeling is similar (and hopepunk can easily overlap with climate fiction), Terra Nil removes the explicit human element. This isn’t Snowpiercer or Claire G. Coleman’s Enclave or even Frostpunk. There’s no kindness or rebellion or collective action. It elides the “-punk” suffix entirely. Should we then brand it “ecohope” or some similarly positive, issues-centered new subgenre?

My gut says no. The reason for that is that, after sitting with Terra Nil and thinking holistically about the experience, I don’t fully buy into its altruistic premise.

The first three biomes feature natural locations: plains and arctic sheets and uninhabited archipelagos, but the fourth is a sharp change. It’s a blasted city. The remnants of skyscrapers poke up out of a ruined maze of land and canals. Up until this point, you could believe that you were a panspermic terraformer, delivering life unto a new planet for the first time. The fourth biome is a revelation: We let things go too far.

It seems to imply that there’s no hope in trying to hold back the slow tide of collapse, that no amount of collective action or kindness will save us from the inevitable… So much for there always being a way out. Any hope lies not in prevention but in a cure.

And what is that cure?

Terra Nil makes no explicit statement about it. The game presents itself simply as a challenge of restoration. Implicit, however, is the means of restoration: the wind turbines, toxin scrubbers, irrigators, calcifiers, and all the other marvelous technologies that allow us to treat this devastated world as a whiteboard. And beyond that, there is the typically game-y approach of providing objectives to tick off on the way to 100% rewilding.

The latter is a paternalistic approach. It tells you that you need a certain volume of ecological diversity in each biome, with additional objectives of reaching certain thresholds for atmospheric temperature and humidity. In that, Terra Nil proves to be not so different from its genre stablemates. It’s less about environmental restoration and more about imposing a human sense of order on the natural world. That approach goes hand in hand with the method of restoration, which is entirely unnatural.

Technology is the solution, proposes Terra Nil. But we’ve heard that — and laughed at it — before. Offloading the responsibility of resolving social ills to expertise and the promise of future technology is tempting. However, in taking this approach, Terra Nil displays a technocratic underpinning. Technocracy is a form of government that places subject experts in control, and technology is increasingly viewed as an integral part of that. Viewed simply, it seems an ideal form of governance, divorced from career politicians and the influence of lobbyists, but it still runs into questions. What makes someone an expert? What knowledge do we prioritize? What consideration is there of the real-world effects of decisions based on theoretical understandings of science and social science?

In Terra Nil, those questions manifest in what you are doing to the environments. It’s restoration, yes, but who is to say that a wetland once existed where one does now? Who is to say that these animals are suited for this location? Who is making the decisions that you are so dutifully carrying out? What makes them right?

It’s an uncomfortable reading of the game, to be sure. Those questions emerge from what’s not said, and the reason those things aren’t said is because of the controlled scope of Terra Nil — which absolutely is a good thing. Nevertheless, the game doesn’t exist in isolation. The moment it pulls back the curtain on its post-apocalyptic setting, it enters into more conversations than its cli-fi premise. And even though it is focused on solutions and giving cause for optimism, Terra Nil has shadows upon its hopefulness.

Published: Apr 23, 2023 12:00 pm