Recent years have seen something of a reappraisal and an attempt to revitalize the classic erotic thriller, as evidenced by the recent spate of television remakes of classic erotic thrillers like American Gigolo or Fatal Attraction. Last week saw the release of Fair Play on Netflix — a movie that is very much informed by and in conversation with the genre.

There is very obviously an appetite for these movies. There has been plenty of discourse around how sexless modern movies are: the award-winning film history podcast You Must Remember This has hosted two separate seasons on the genre – “Erotic ’80s” and “Erotic ’90s” – and even the Toronto International Film Festival programmed a season of screenings of classic erotic thrillers. However, the erotic thriller is a particularly prickly genre that is hard to update for the modern world.

Recent years have seen a number of these movies released on streaming: The Earthquake Bird, Deep Water, The Voyeurs. However, the reception has generally been muted. Part of this may simply be the fact that they were released on streaming, and so never got to dominate the zeitgeist — watching an erotic thriller in a packed cinema is a very different experience from watching it on a laptop. However, part of it may also just be the passage of time. This is a very different world.

Many of these projects feel disconnected and lifeless, lacking the electricity that made earlier examples of the form so compelling. In her review of Deep Water, Amanda Hess noted that veteran erotic thriller director Adrian Lyne “doesn’t seem to understand what time he is living in, and it shows.” It is a challenge. Gender politics have changed significantly over the past few decades, and so it’s tempting to wonder whether the template of the erotic thriller is fit for purpose.

However, Fair Play, the feature directorial debut of Chloe Domont, works in large part because it plays so many of the classic tropes relatively straight. Like many of those 1980s classics, Fair Play unfolds in the world of New York finance. It juxtaposes its repressed and sterile office surroundings with its leads’ hot-and-heavy action between the sheets. Emily Meyers (Phoebe Dynevor) and Luke Edmunds (Alden Ehrenreich) are analysts at a high-profile hedge fund engaged in a secret affair. Luke asks Emily to marry him, and she agrees.

However, their relationship is disrupted when Emily receives a promotion that Luke was expecting. Luke finds himself working for Emily. Although he is initially supportive and encouraging, he gradually becomes hostile and aggressive. As Emily ingratiates herself to her bosses Campbell (Eddie Marsan) and Paul (Rich Sommer), Luke begins to suspect that he has been marginalized and undermined. He feels emasculated and undervalued, and the tension between the two builds to boiling point.

This is all fairly standard stuff. It doesn’t so much evoke a generic erotic thriller, as it resonates with a very specific subgenre within the larger template. In the early 1990s, there was a wave of erotic thrillers that were particularly anxious about the threat posed to male employees by career-minded women, especially sexually aggressive career-minded women. The Temp, The Last Seduction, and Disclosure were all about this particular masculine anxiety.

The erotic thriller was a product of the 1980s. It was a fundamentally conservative genre, one that existed in the larger context of a backlash to feminism. In some ways, the erotic thriller could be seen as a companion to the puritanical slasher movies of the era, in which men with knives punish sexy women for their perceived promiscuity. It’s no wonder that Barry Keith Grant lumps together erotic thrillers like Fatal Attraction, Poison Ivy,and The Temp under the banner of “the Yuppie Horror Film.”

Michael Douglas would become the avatar of the genre, starring in examples like Fatal Attraction, Basic Instinct, and Disclosure. Douglas embodied a certain form of rugged Reagan era masculinity. Coupled with his work in other era-defining films like Wall Street and Falling Down, Douglas would come to serve as “the representation of flawed, crisis-ridden masculinity and the concomitant decline of male cultural and social authority” during the 1980s and into the 1990s.

In Fatal Attraction, Douglas plays Dan Gallagher, a married New York lawyer. Dan begins an illicit affair with a woman named Alex (Glenn Close), an editor at a publishing company. Inevitably, Dan bites off more than he can chew. Alex becomes increasingly unhinged, eventually posing a threat to Dan’s professional and personal security. In the end, after breaking into the family home, Alex is shot and killed by Beth (Anne Archer), Dan’s wife. The nuclear family is preserved. Order is restored.

Fatal Attraction was originally scripted to be sympathetic to Alex, acknowledging that Dan had been the one to transgress by breaking his marriage vows. However, adapting his own short film Diversion, writer James Dearden was forced through revisions to make Alex more cartoonishly evil. It worked. Close has described reading headlines describing Alex as “the most hated woman in America.” Test screenings pushed Paramount to embrace a particularly brutal ending. “They want us to terminate the bitch with extreme prejudice,” noted studio executive Ned Tanen.

Alex became an archetype for a new form of female character. She was competent, aggressive, and untrustworthy. “This trope of mendacious women is rooted in an alarmist reaction to feminist gains,” observed Beatrice Loayza. “In the eighties, the good old days of horny-bastard-style seduction (i.e., harassment) seemed to be under attack, and many men feared that feminists, hellbent on social climbing, could cry wolf and accuse anyone, guilty or not, of foul play.” After the film’s release, Douglas conceded, “If you want to know, I’m really tired of feminists, sick of them.”

As such, Fatal Attraction was the story of a very masculine set of anxieties, in response to the feminist gains over the previous decades. The men in these stories were often professionals who found themselves confronted with women who were just as ruthless and just as promiscuous as they had been. There was a palpable fear that the combined forces of the sexual revolution and the entry of women into the white-collar workforce had rendered men redundant.

This fear became particularly pronounced in the early 1990s, particularly in the professional sphere. In 1991, Anita Hill testified about the sexual harassment she received from Clarence Thomas. Even beyond drawing attention to such threats in the workplace, her testimony was credited with “revitalizing feminism.” The following year, a record 47 women were elected to the House of Representatives, in what was described as “the Year of the Woman.”

The backlash came quickly. Released in 1993, The Temp is the story of Peter Derns (Timothy Hutton), a recently divorced father who is assigned a beautiful Stanford-educated personal assistant named Kris Bolin (Lara Flynn Boyle). Inevitably, Kris reveals herself to be a ruthless sociopath willing to do whatever it takes to get ahead. The following year, The Last Seduction focused on Bridget Gregory (Linda Fiorentino), who plots to turn a job at an insurance company into a murder-for-hire gig.

By 1994, “the Year of the Woman” had given way to “the Republican Revolution,” with the Republicans taking control of the House of Representatives and the Senate. That same year, Douglas starred in Disclosure. He played Tom Sanders, a production line manager sexually assaulted by his boss, Meredith (Demi Moore). Disclosure is a movie that, to quote Travis Woods, is “thoroughly aroused by women and yet seeped with a marrow-rooted resentment of their encroachment into male territory.”

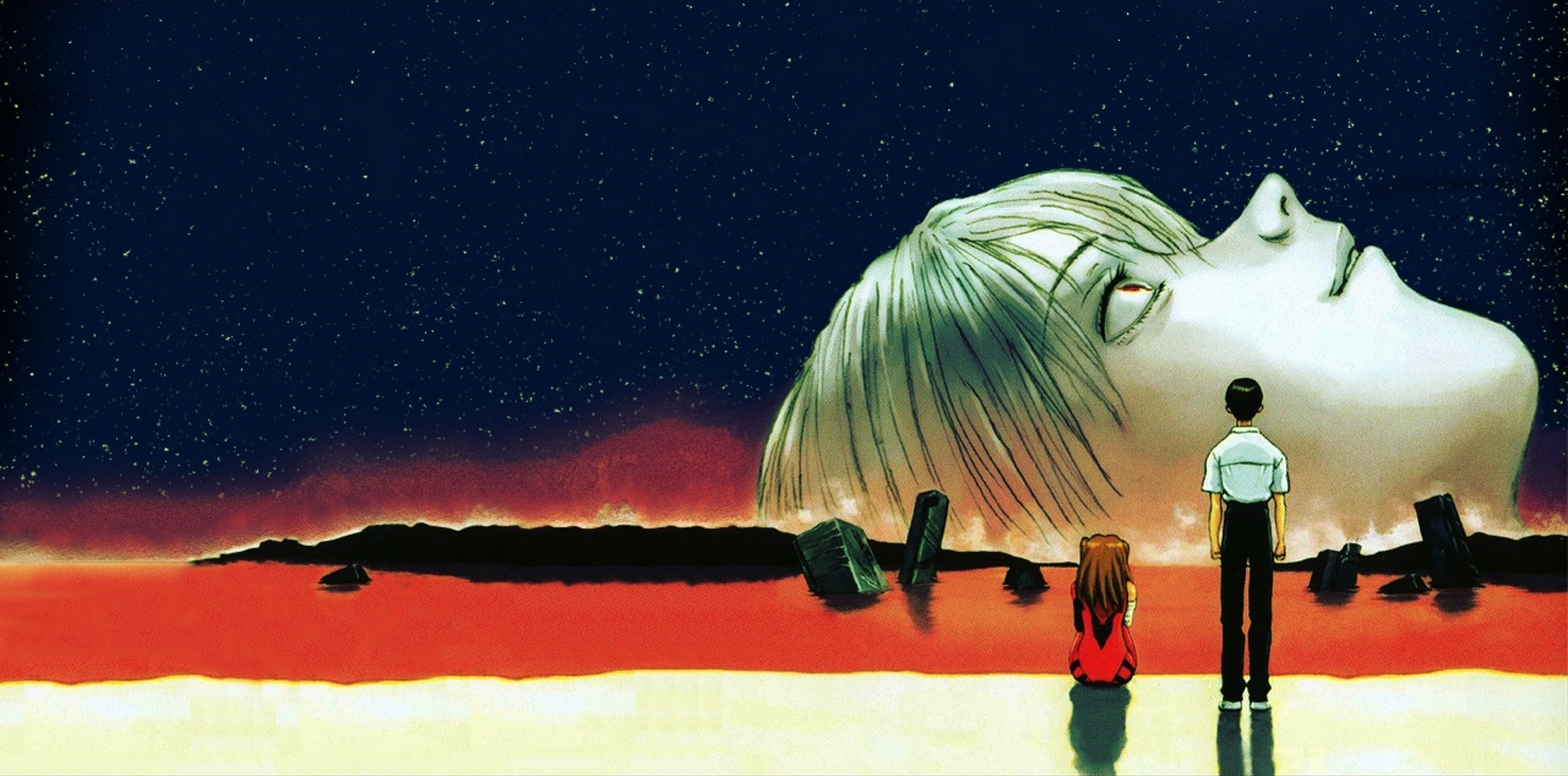

Fair Play takes that familiar template and inverts the character arcs. It is a story that is inherently sympathetic to a young sexually active professional woman confronted by masculine anxiety. Over the course of the film, unable to deal with Emily’s success and his own stalled career, Luke unravels and becomes increasingly unstable. Ehrenreich isn’t channeling Douglas’ performance from Fatal Attraction. If anything, he’s evoking Close as the sexy and seemingly charming white-collar worker who appears to have it together, until he doesn’t.

This approach also allows the film to acknowledge and engage with what so many of these erotic thrillers were actually about. It explores the consequence of that masculine anxiety. After all, more than half of all female homicide victims in 2017 were killed by intimate partners or relatives. As a quote attributed to Margaret Atwood notes, “Men are afraid that women will laugh at them. Women are afraid men will kill them.” This male insecurity is a greater threat to women than any feminist intrusion into conventionally masculine spaces.

Fair Play emerges into a post-#MeToo landscape not so different from the climate that created Disclosure. Christine Blasey’s allegations of sexual assault against Brett Kavanaugh prompted comparisons to the Anita Hill testimony. Just as the 1990s saw a moral panic over the supposed erosion of “family values” that informed those erotic thrillers, modern America is in the grip of a similar fervor. However, Fair Play is the product of a cultural movement with a deeper understanding of context.

“This isn’t really a film about female empowerment,” concedes director Chloe Dumont of Fair Play. “This is a film about male fragility.” Just as Alex embodied an exaggerated set of fears about contemporary women, Luke represents familiar anxieties about modern masculinity. Lacking the skill to advance his career, he refuses to confront his inadequacy. Instead, he falls down a YouTube rabbit hole, embracing the teachings of motivational speaker Robert Bynes (Patrick Fischler).

Indeed, if there is an issue with this gender switch within Fair Play, it’s the reluctance to allow Emily to fully embrace the moral ambivalence embodied by Douglas in movies like Fatal Attraction or Basic Instinct. At the climax, Emily lies about her relationship with Luke to protect her career, but this comes after Luke has so thoroughly self-sabotaged as to render himself radioactive. For most of the movie, Emily is the perfect and loving fiancée, indulging Luke’s insecurities and championing him even as he refuses to accept her help.

In his erotic thrillers, Douglas was allowed to play flawed human beings while retaining audience sympathy. Douglas has acknowledged the contradiction of Fatal Attraction, where he could “start off as an adulterer, and ultimately the audience is rooting for [him].” In contrast, Fair Play is more careful to ensure that Emily remains “likable,” perhaps acknowledging the double standard that female characters and actors face from certain audiences. Still, this is a minor and understandable criticism.

To be fair, Fair Play is not the first film to be built around this basic reversal. Both Un Homme Idéal and The Perfect Guy attempted something similar in 2015. Shows like You are also built around a similar concept. Still, Fair Play feels somewhat sharper because of its professional setting. It uses a clever role reversal to demonstrate that there’s still life in the classic erotic thriller. The template is as solid as ever, with a little shift in emphasis serving to refresh a familiar framework.

Published: Oct 11, 2023 11:00 am