Since they first appeared on the scene in 2007, Vanillaware have been underdogs. Coming from a small group of developers from Atlus led by George Kamitani, Vanillaware believed in the power of original games and 2D artistry in an industry that had increasingly become less interested in both. Each of their games is entirely distinct from one another except through the almost slavish devotion to hand-drawn 2D artwork and they will take years to perfect their games. In short, there’s nothing quite like a Vanillaware game.

Last month, a lot of players probably had their first introduction to Vanillaware through Unicorn Overlord, a strategy RPG that has already sold over 500,000 copies in a month. Given the niche status of their games, this surge of success was most likely due to positive word of mouth as most of their games tend to gain popularity after being released. While their games may not be the most popular and tend to become hidden gems, to me, their output of classic yet modern JRPGs are my comfort food. They’re easy to get into, provide a warm and cozy feeling, and leave you feeling immensely satisfied.

Each game created by Vanillaware comes from a deeply personal place from their staff. While we live in an age where most major companies pump out yearly or bi-yearly releases for titles to hit quotas and churn a profit, Vanillaware takes its time developing their games and even then aren’t usually sales juggernauts. Unicorn Overlord, for example, took eight years to make and while its 500,000 copies sold is nothing compared to Dragon’s Dogma 2’s selling 2.5 million in less than two weeks, those numbers are impressive for Vanillaware. Despite that, they aren’t afraid to take big risks and swings, sometimes to negative effects, but they stand by their ground and stand by the games that they want to make.

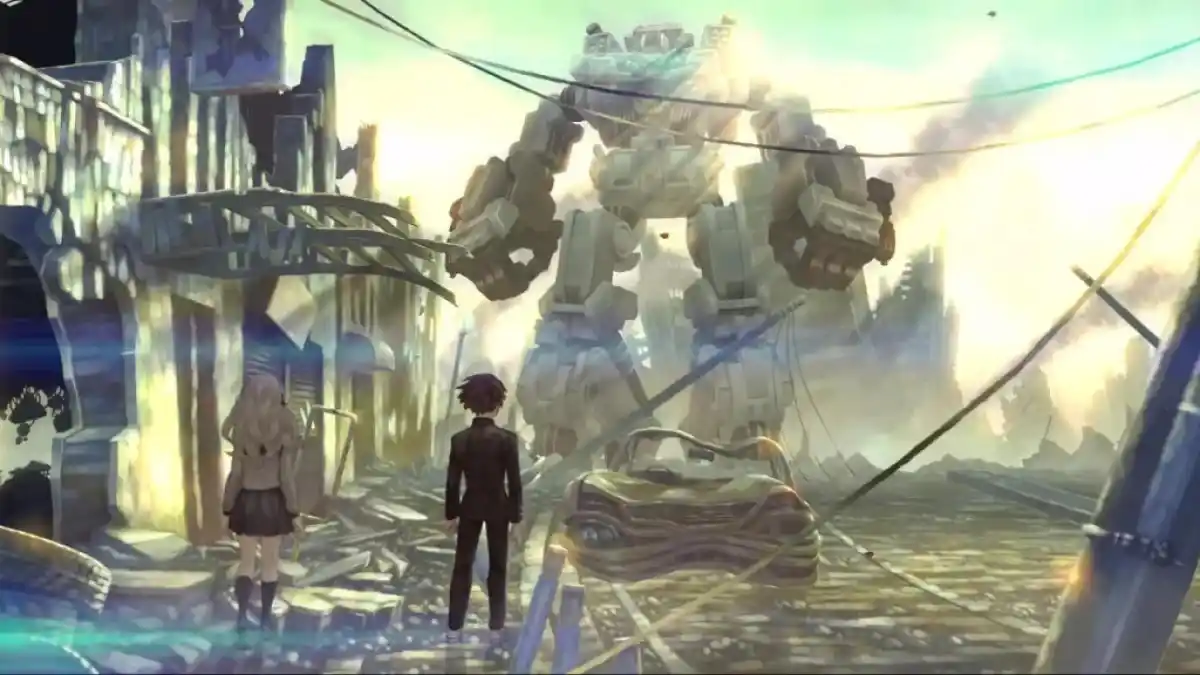

As a company, six of their games have made it to the West – GrimGrimoire, Odin Sphere, Muramasa: The Demon Blade, Dragon’s Crown, 13 Sentinels: Aegis Rim, and now Unicorn Overlord – and each game feels like it’s been polished to a mirror shine. Almost immediately upon starting any of those six games, the first thing that hits you is the visuals. You can tell a Vanillaware game solely by its aesthetic, with incredibly detailed 2D worlds, intricate character designs, and areas that are bursting with color. I cannot stress this enough when I say that games like Muramasa: The Demon Blade and Dragon’s Crown are genuine works of art, if only because I can take a screenshot of any moment from the game and marvel at all of the elements at play.

Take the food, for example. Both of those aforementioned games make it a point to have food as a central mechanic to increase your experience points and level up. Each game gives us intimate close-ups of each dish and takes pleasure in showing how they’re prepared and the characters slowly eating and savoring the dishes. It hits the same vibes that you get when you look at Studio Ghibli food. You just look at it and can’t help but want to dig into each and every dish that appears on screen. They’re just so mouthwatering and there’s just something so comforting about being presented with a delicious warm meal, even if it is a fictional one. You feel like a guest when you’re playing a Vanillaware game and they’re a gracious host treating you to some of your favorite meals.

Because of this, there’s just a sense of nostalgia that permeates across all of Vanillaware’s games. It’s not even for how they stir up your own memories about food but for their emphasis of 2D animation, straightforward level design, and simple yet effective gameplay loops. We live in an era where CGI is the standard and older animation styles, like 2D art, stop-motion, and pre-rendered backgrouns are seen as antiquated. CGI is far easier to do and you only need to look at how much time and effort was spent animating a movie like Who Framed Roger Rabbit? or the years that were dedicated to bringing about the dioramas used in Hironobo Sakaguchi’s Fantasian and understand why some studios, both in Hollywood and in the game industry, would favor easier animation styles.

Projects like that take time and while it certainly isn’t easy to learn how to use animation techniques from film studios like Pixar or game developers like Square Enix, it’s even harder to make projects like those Vanillaware does.

Because of that, Vanillaware games come across like modern-day PS1 games. I don’t mean that from a graphical perspective like with 5th generation homages like Crow Country or Corn Kidz 64, but from a design perspective. There’s limited interactivity with a Vanillaware game, maybe not to the same level as pre-rendered backgrounds were during the PS1 era, but there’s a reason that nearly all of Vanillaware’s library are limited to 2D games. That may sound like a negative, but it gives a sense of identity to Vanillaware games that set it apart from all others. They’re the masters at creating 2D games with wonderful animated modern visuals that do present restrive worlds, but also just that restriction to create simple yet effective gameplay loops. I think that’s where the core of their nostalgic appeal lies – if you’re someone that loves PS1 era JRPGs, then there’s something about a Vanillaware game that just clicks with you.

Odin Sphere is a prime example of this. As a 2D action JRPG, you navigate very flat and oftentimes basic rooms while fighting a never-ending stream of enemies. You have an attack button, a jump button, a special attack button, and a button to open your item menu. That’s all you have to work with, but it becomes deciding complex when you start to add directional inputs into the mix. You could just mash the square button to lead you to victory, but if you treat Odin Sphere almost like a fighting game, you can string together impossible combos to decimate any enemy that gets in your path, unleashing a flurry of blows that feel so damn satisfying. It really does scratch that part of your brain where you like to see all of the damage you do to a group of enemies in one, beautiful combo.

A Vanillaware game is a game that anyone can play, and it’s easy for anyone to master. There’s a very high skill ceiling for how effectively you can play their games, and it all comes from how simple it is to actually pick up and play them. You don’t need to learn several intricate mechanics in order to just be competent in a game like Odin Sphere. You just need to understand the basics and then you can play around with the rest as you see fit. Even if you struggle, it never feels punishing and that you aren’t good enough. You’re set back a little bit, but the game picks you up and encourages you to try again. I don’t find myself getting stressed when I play a Vanillaware game, even if the stakes are high in the plot. I can just focus on having fun as my mind goes back to an era where strong gameplay loops were the priority.

That does beg the question though if Vanillaware games are all style over substance, and I won’t disagree with those assessments. Yes, their games are, for the most part, pretty simplistic and on the surface don’t offer as much depth as other JRPG or action games. I can attest that while I was playing through Muramasa: The Demon Blade and GrimGrimoire I found myself getting bored of the game by the end and relying on the same basic moves and strategies to beat every enemy encounter and really only kept playing to see what setpiece would happen next and to see the artistry on display. And yes, at the end of the day a video game is meant to be played and not watched, but by making their games so easy to understand, you can have the best of both worlds. You can have an easy game that you can sit back and play while also appreciating all of the design elements put into it. The two elements exist, but they’re not directly interfering with each other.

But I think what makes a Vanillaware game so comforting to me is that it’s clear that they care about their games. Each time they’ve rereleased any of their games, which they’ve done for their first four, they’ve always taken fan feedback into account, whether it be tweaking some minor gameplay elements or introducing new mechanics to streamline the user interface. They want to make sure that all gamers can play the best version of their games and it does my heart well to see a game company that actually cares about their final product. Vanillaware, like an expert chef, takes time preparing their meal and doesn’t rush just to get food on a plate. When they do, they’re open to feedback to improve their skills and then make sure the next time you visit them they’re even better.

I know that if I ever sit down to play a Vanillaware game, whether it be an older game like Odin Sphere or with the recent Unicorn Overlord, I know for a fact that it’s made with love and attention to detail. No element is overlooked and I can sit back and know for a fact I’m going to enjoy their games not only because of how compelling their visuals are, but because of how easy it is to enjoy myself while playing them. If that isn’t the same as comfort food, I don’t know what is.

Published: Apr 9, 2024 09:00 am