Frank Herbert’s original series of Dune novels is, amongst other things, a tale of cycles. The titular planet is transformed from desert to a verdant green land, then back to desert over the course of six books. So it must be with Dune video games, as the franchise rose to dominate the real-time strategy landscape in the ‘90s, went on an indefinite hiatus in the ‘00s, and is now beginning to make a comeback — starting with Dune: Spice Wars, a 4X real-time strategy from Shiro Games.

Spice Wars entered early access last week with an impressive debut build. It’s stable, runs well, and already passes the all-important “just one more turn” test for compulsively moreish gameplay, even if strictly speaking there are no turns. You pick one of four currently available factions – Atreides, Harkonnen, the Smugglers, or the Fremen – and embark on a freeform campaign that wouldn’t feel out of place next to any classic 4X franchise, like Civilization or Galactic Civilizations. The main difference with those franchises is that, although there is a pause button, decisions in Spice Wars play out in real time, so there is an added urgency and pressure to the gameplay.

The real-time elements are also a smart nod to Dune’s RTS heyday that don’t feel like a retread of those older titles. They are not the only callback either. The soundtrack is a suitably mood-setting mix of synths that references Frank Klepacki’s work on Dune II and its reimagining, Dune 2000.

The art isn’t up to par with something like Amplitude Studios’ beautifully drawn Endless series, but it’s evocative nonetheless. The desert in particular looks phenomenal — sand clouds obscure the map in a fog of war until scouted by an ornithopter, giant craters and plateaus interrupt purple-and-red spice fields, sandstorms blanket entire regions, and crashed vessels present exploration opportunities. The game does an excellent job of conveying the sense of a mysterious, dangerous, and unforgiving landscape without ever succumbing to monotony.

The aesthetics underpin a number of more or less complex gameplay systems. Unsurprisingly, the spice Melange is at the heart of Dune: Spice Wars. In Dune’s fiction, it is a drug found only on the desert planet that makes interstellar travel possible, by enabling the Spacing Guild Navigators to enter a state of prescient awareness to search for safe routes between the stars.

Therefore, no matter which faction you pick, your first task is to establish a spice supply. This first requires the conquest of a region, which in turn means recruiting some military at your main base and then sending them to that region’s controlling settlement. The ensuing battle has little strategy to it and relies almost entirely on relative unit strength. Send two early-game units against a village defended by three squads, for example, and you are pretty much guaranteed to lose.

Spice can be stockpiled to pay a tax to the Emperor or a bribe to the Spacing Guild. In line with the source fiction, the Navigators’ prescience allows them to observe unsanctioned activities, but they value the flow of spice above all other political concerns. Therefore, they can be bought off if you are playing as the Fremen and mining spice without the Emperor’s knowledge or permission.

Alternatively, spice can be exchanged into Solari, the game’s only monetary currency. It can be a delicate balance to strike. On one hand, there are penalties for not paying your taxes or bribes, and certain events and diplomacy options require a healthy stockpile of the drug. On the other hand, most things are bought at least partially with Solari and require Solari for upkeep.

Other resources include plascrete as building material (an odd choice of terminology, given that Frank Herbert’s novels relied on plasteel, and plascrete was apparently introduced in Brian Herbert’s fiction), manpower to generate troops and spice mining crews, fuel cells to power buildings and certain high-end technology, water, and authority to spend on conquest. Some resources are even more abstract, such as standing in the Landsraad (the body that represents Dune’s various houses, like the Atreides and Harkonnen), additional influence in the Landsraad, knowledge to spend on research, intel that is used on espionage actions, and hegemony, which is used to measure overall power and progress towards one of the game’s victory conditions.

It’s an initially dizzying array of variables to keep track of, particularly as you start to notice slight faction variations, (The Fremen do not use fuel cells, for example.) are offered a regular vote in the Landsraad, recruit agents to send on espionage missions, face scripted events to take part in, and learn various combination options. Build a wind trap in a region that has a wind strength of 4, for instance, and that wind trap will produce 12 water instead of the base 3.

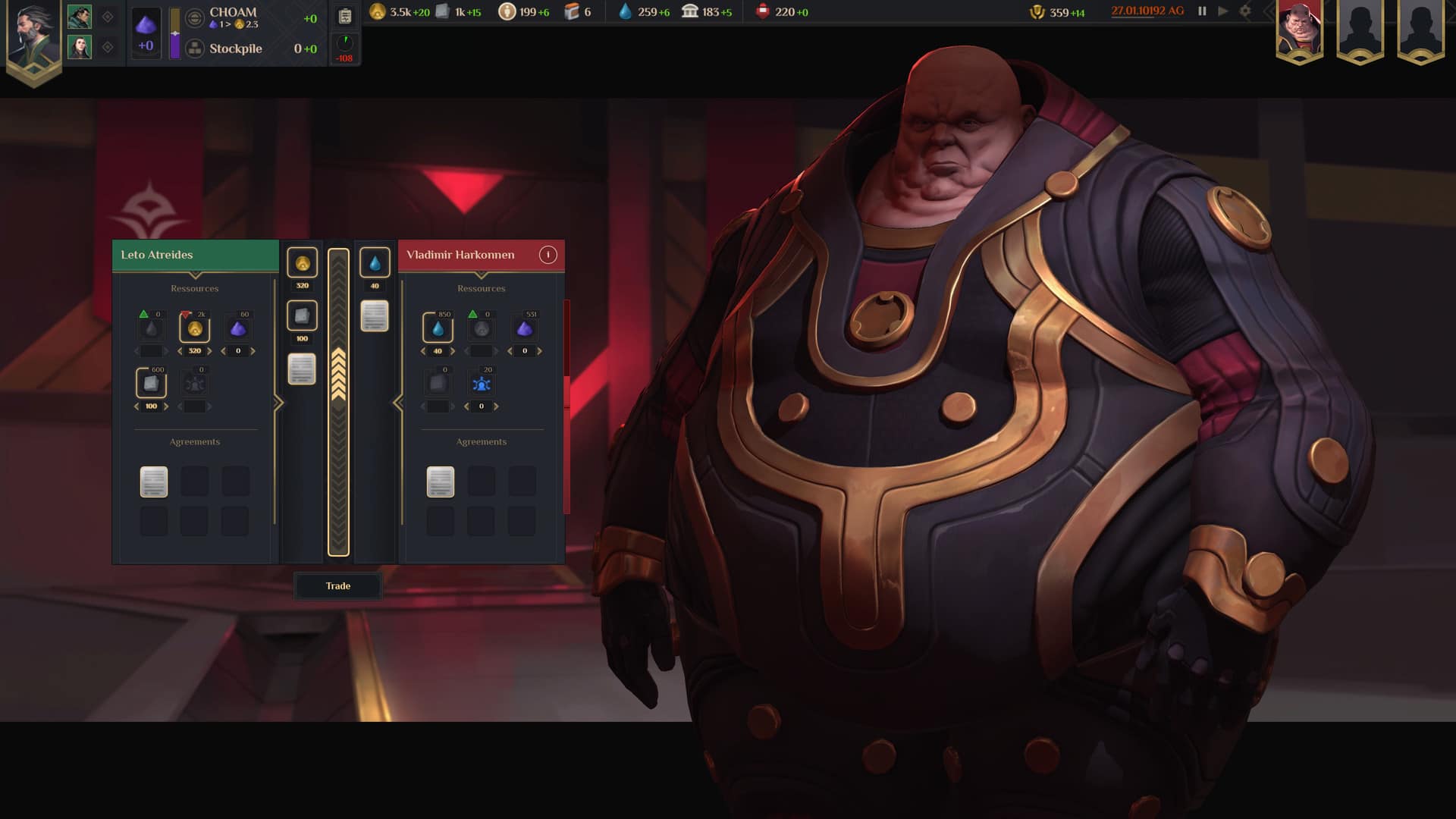

However, after a few hours, the limitations begin to rear their disappointing head. With the notable exception of a few cross-genre titles like Sins of a Solar Empire: Rebellion, combat and diplomacy have long been the Achilles’ heel of the 4X genre. But they are especially basic in Dune: Spice Wars at the moment. Even in the late game, unit variety doesn’t fundamentally change the numbers game you play in the opening hour. And diplomacy boils down to little more than flinging resources and treaties at rival factions.

This is especially disappointing given the importance of diplomacy in Herbert’s fiction. After all, the first novel effectively ends with the meeting of a diplomatic council, while the sequels have countless scenes that take place in audience chambers, embassies, petitions, and so on. This speaks to a wider issue with Spice Wars.

Shiro Games certainly uses all the Dune terminology correctly (except maybe that plasteel/plascrete issue) and clearly has a handle on the lore, but none of it feels inextricably integrated into the gameplay. You could change spice to gold reserves, Solari to cash flow, and the Spacing Guild to the taxman, and the underlying system would feel at home in a modern day city-building simulator.

Eventually you start to feel the absence of other important players from Herbert’s books. Where are the Bene Gesserit, the Tleilaxu, or the Ixians? Wouldn’t it be great, for instance, to defy the advice of a Bene Gesserit counselor, purchase a ghola as an espionage agent, and send them to impersonate a member of the Imperial House? Where, for that matter, is the Imperial House Corrino? I can pay them taxes, but I can’t play as them or engage them in diplomacy.

Some of these elements aren’t altogether absent from Spice Wars, but they are exceptionally limited in the current build. When starting a campaign, you get a choice of advisors, which can include some mentats and Bene Gesserit. However, the mentat is not someone to draw on for on-the-fly calculations of probable outcomes during the campaign, but simply a pre-game statistic modifier. Likewise, the Bene Gesserit cannot be used to more accurately read someone during a diplomatic meeting or to try to predict a future outcome — she, too, merely changes some overall gameplay statistics.

These problems aren’t insurmountable. Avalon Hill’s 1979 board game Dune (recently reprinted by Gale Force Nine) directly integrates each of its playable factions’ defining characteristics into the gameplay. The Bene Gesserit, for example, steal the victory if at the start of a campaign they accurately predict which faction will win the game.

Nonetheless, it may well be that Spice Wars’ limitations point to a broader problem with the Dune license. Just as for many years it was claimed that the novel is unfilmable, perhaps we are now finding that Frank Herbert’s fiction cannot be rendered into a video game without sacrificing some of its deeper themes and complexity.

Darren Mooney has argued in an excellent essay for this publication that, contrary to initial appearances, Dune is not a chosen one “mighty whitey” narrative. One of the reasons for this is that Paul Atreides, Dune’s protagonist, is ultimately a failure. Not just a failure — by the time of the second and third Dune novels, he is the most genocidal leader in the history of humanity. In Dune: Messiah, Paul laments that his leadership and cult of personality have led to over 60 billion deaths, the sterilization of 90 planets, the moral downfall of more than 500 other worlds, and the erasure of over 40 religions. That doesn’t make for a very happy marriage with a gameplay loop premised on conquest and domination, especially when that loop is supposed to lead to a satisfying and enjoyable victory.

Dune is also a study in the importance of ecology and ecosystems. Indeed, some have argued that Dune is one of the earliest examples of climate fiction — a currently popular genre that tends to focus on climate change issues. There is an entire chapter, which was greatly simplified for the recent film, in which Dune’s ecologist and the Fremen faction leader in Spice Wars considers the relationships between the planet’s giant sandworms, their habitat, and spice. There are many choice lines, but here is one: “You cannot go on forever stealing what you need without regard to those who come after. The physical qualities of a planet are written into its economic and political record.” How does one reconcile such sentiments with gameplay mechanics that are premised on the unthinking and inconsequential exploitation of a planet’s natural resources?

Then again, it’s not like these themes haven’t been tackled in video games, albeit separately and in vastly different titles. Look no further than Crusader Kings 3, for example, for a set of systems that are able to model the complexity of leadership, including its frequent vanity, insanity, and ultimately failure — where personal and dynastic survival and ambition often outweigh the needs of the governed population. Or consider Terra Nil, a simplistic but effective “reverse city builder” about ecosystem reconstruction.

Neither example should be taken to imply that the next Dune: Spice Wars update should receive a Crusader Kings-style overhaul. However, I would pay good money for DLC that lets you play as a 3,500-year-old gradually evolving man-sandworm hybrid.

Published: May 4, 2022 11:00 am