The Legend of Korra wasn’t so much subversive as it was respectful of its younger viewers.

The Legend of Korra reached its series finale last month, bringing an end to the universe that started with Avatar: The Last Airbender. From the beginning, Korra differentiated itself from Avatar with an older cast, a drastically different personality for its Avatar, and a world transformed by ATLA’s heroes. Most significantly, LoK spoke to its viewers, young and old, with a more mature voice as it handled issues often reserved for older audiences.

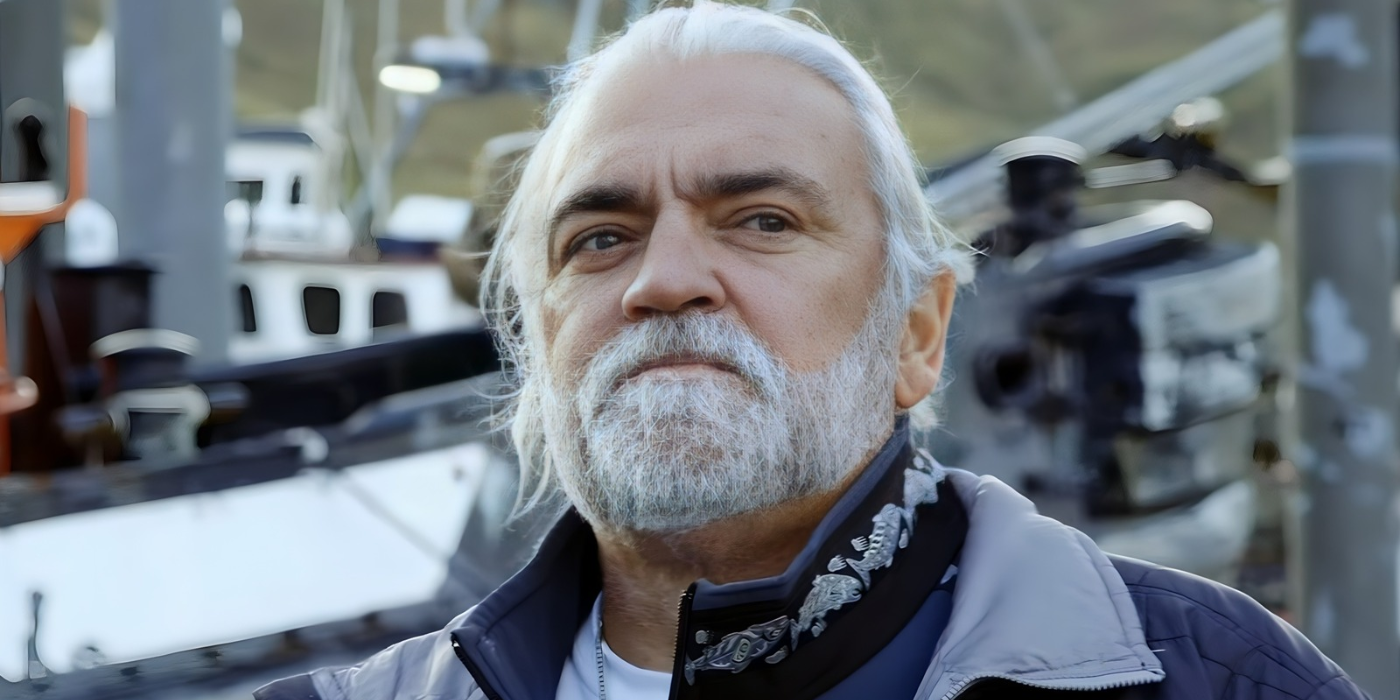

A fantastic piece from Variety called the show “subversive” for telling these stories on a children’s network, but that may not be the best word to describe the series. While Legend of Korra certainly dealt with topics most any children’s show would shy away from, it would be difficult to argue that the series sought to subvert anything. As Michael Dante DiMartino, one of ATLA and LoK’s co-creators posted after the finale:

While the episodes were never designed to “make a statement”, Bryan and I always strove to treat the more difficult subject matter with the respect and gravity it deserved.

Most of Korra’s fans appear to be young adults (thanks to forums and Tumblr), but there were still plenty of children and younger teens watching the series through its conclusion. Legend of Korra didn’t approach the more serious content with an agenda of subversion – rather, DiMartino and Bryan Konietzko (the other co-creator; collectively they’re called Bryke) respected those younger viewers and their ability to process the show’s more mature stories.

Refusal to approach mature subject matter not only puts restrictions on the storytelling process, it sanitizes the final product. After all, kids already know death, depression, and terrorism exist, so why can’t their shows speak openly on these ideas? Thankfully, the people behind Legend of Korra acknowledged that younger viewers can handle this kind of subject matter and the narrative was spun with more freedom than many Nickelodeon cartoons, or even Avatar.

If you haven’t, check out our review of the finale or peruse our reviews of the third and fourth seasons.

Spoiler Warning: Nothing is safe beyond this point.

Death

The pivotal moment that kicks off events in ATLA and Korra is the genocide of the Air Nation by the Fire Nation. Still, even with mass murder being the spark that set off of the first series, the genocide is handled largely in the abstract (although Aang’s mourning is especially poignant and well-done). Avatar never really became comfortable with death, and in fact the vague delivery of one character’s demise turned into a joke later on in the series.

Legend of Korra, however, did not shy away from character death. A murder-suicide closed out the first season and the audience watched the air pulled from the Earth Queen’s lungs in the third. As far as Korra was concerned, Bryke seemed to understand that kids weren’t going to be traumatized by on-screen death. The writers explored the story of these characters freely and – at times – lethally. While occasionally clichéd, these deaths often brought significant emotional weight to the story.

That murder-suicide was ultimately the result of severe emotional and physical abuse by the father of the first season’s antagonist(s?). The murder of the Earth Queen by Zaheer was a turning point for the audience as first moment we learn how dangerous the anarchist really was. His paramour, P’Li, suffered one of the most brutal and sudden deaths in children’s television, and it was delivered shortly after an incredibly humanizing scene between the two of them.

Sure, sometimes characters died to get them out of the way for the next season’s villain, but even some of those deaths functioned to establish the humanity of the show’s many antagonists.

Sympathetic Villains

The primary antagonist of Avatar: The Last Airbender was pretty much just an angry guy that wanted to rule the world. In Korra, however, all of the villains are refined with backstories and fairly tragic situations. Their motives were usually understandable (except for Unalaq; screw that guy).

The showrunners trusted that the audience, including all those kids, could comprehend that the “bad guys” usually see themselves as the heroes. All of Korra’s nemeses eventually take things too far, losing a lot of our sympathy once they are revealed to be bloodbenders or they build a super-weapon, but even Amon and Kuvira have heartbreaking backstories to help the audience feel some compassion for them.

Korra provided great background on what motivated these characters, rather than just the standard goal of “ruling the world” (once again, except for douchelord Unalaq). Amon was a victim of severe abuse and manipulation at the hands of his father, Zaheer was witness to the fumbling of the world leaders and atrocities in the Earth Kingdom, and Kuvira’s abandonment issues gave a reason for her need to control. Zaheer and Kuvira were particularly human characters thanks to their personal, romantic attachments, but both lost the ones they loved in the journey to reach their goals.

For much of each villain’s season they present valid arguments for their actions. For instance, the first season of Korra made a terrorist someone you could kind of understand. Not because Bryke was trying to teach kids anything about terrorism, but because they respected that those younger viewers could resolve the dissonance between understanding someone’s view and disagreeing with their methods.

Depression

Just as Legend of Korra would humanize its villains, the hero of the series was similarly put through struggles most kid-friendly TV would avoid: in this case, depression.

Heroes deal with self-doubt and sadness in almost any story. In ATLA, one of the dominant themes was Aang’s internal conflict over assuming the full responsibilities as the Avatar and his seemingly inevitable fight to the death with Firelord Ozai. Korra went through similar issues, such as doubting her ability to airbend, but at the end of the third season Korra was stricken with full-on depression.

After her nearly fatal battle with Zaheer, Korra is left in a wheelchair from her injuries and the last shot of the season is of our hero crying quietly at a joyous ceremony for her friend. Much of the fourth season addressed Korra’s struggle to heal from the emotional damage of her confrontation with Zaheer, with the episode “Korra Alone” chronicling most of her three year journey.

Depression is a serious and unfortunately common issue, but it is still largely unaddressed in media, and especially not addressed in children’s shows. Legend of Korra respected the weight of the issue, and while it didn’t explicitly say what depression is or how to treat it, by showing the hero of the series dealing with and recovering from it, perhaps mental health issues might be normalized (and less oppressive) for those younger viewers.

Queer Representation

The Legend of Korra ends with Korra and Asami, her long-time female friend, walking hand-in-and into the spirit world together. For many this was a clear indication of the two women entering into a romantic relationship, and later the creators confirmed the idea. The final scene signified the beginning of a romantic relationship for Korra and Asami.

The idea of ending the series with these two together was something Bryke had considered (according to their posts), but they didn’t think they could do it given the network. Leading up to the finale, many fans shared this expectation; Nickelodeon would never allow for a same-sex relationship in one of their cartoons, right?

As Konietzko wrote in a Tumblr post, sometimes characters tell the writers what they need to do, and apparently that is what happened with Korra and Asami’s relationship. If this was any other animated series with a young audience, Korra wouldn’t have ended up romantically involved with anyone (or maybe with former beau Mako). But Legend of Korra isn’t another show, and its creators wanted to take the story this direction.

Bryke didn’t put Korra and Asami into a relationship to subvert anything. These characters ended up together because it felt right for the writers and they knew their younger viewers could understand it. Most kids are not strangers to the concept of same-sex relationships. Plenty of families include members of the LGBTQ community and many more as part of their neighborhoods. Hell, some of the kids watching Korra aren’t straight, even if they haven’t reconciled that within themselves or with their family.

So yeah, kids know that gay people (or in this case, bisexual people) exist. They can process that idea just fine and like many other topics The Legend of Korra addressed, Bryke understood this and respected the maturity of their younger viewers.

Published: Jan 8, 2015 7:00 PM UTC