There’s a rule that composer Gareth Coker follows whenever he writes a piece of music: If it doesn’t make him feel the emotion he’s trying to get across, he never bothers sharing it. Emotion is the entire point, and he doesn’t want to waste anyone’s time with a piece of music that he knows doesn’t accomplish his goal.

“I just keep going until I feel what’s appropriate for the scene,” said Coker. “Once I get there, hopefully it translates to all of the other people who are playing the game.”

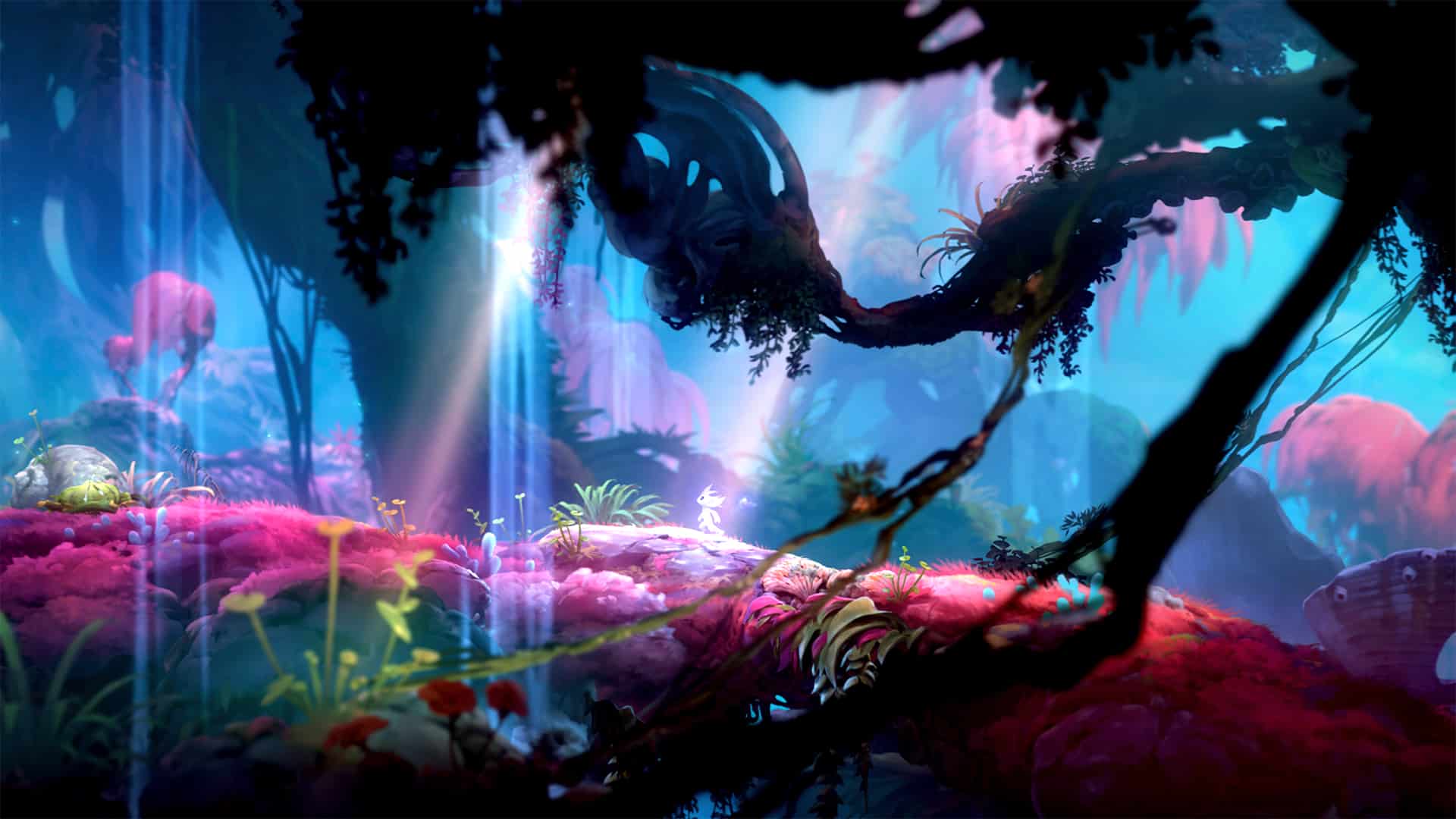

It’s a philosophy that makes sense coming from the man who composed the scores for both Ori and the Blind Forest and Ori and the Will of the Wisps. The games were made with a barbed arrow aimed directly at players’ hearts, and judging from the reactions of players and critics alike, both games hit the mark. The music played a clear part in this, accompanied of course by memorable characters and gorgeous art and animation filled with personality.

Coker was brought in by developer Moon Studios from the very beginning of both games’ creation, with the goal of making sure that the music fit with every area, moment, and possible gameplay style. He worked closely with the entire team over the course of the games’ development, studying the story beats, looking at art assets, and watching how people play the game to make sure everything fit perfectly.

“It just allows me to make so many more decisions, like learning the speed of the gameplay helps me make a decision on tempo and pacing of the music,” Coker said. “Then I get to see the environments and the artwork early, which helps me start to make choices about instruments that help me generate the right sound palette for each area.”

Coker worked most closely with the artists and animators when it came with the game’s cutscenes, which required a lot of collaboration.

“The cutscenes are storyboarded. Then I write the music to the storyboards, which is super rough and not tight — don’t need to be timed accurately at all,” said Coker. “Then the animators will go back and time the sequence to the music. It’s just kind of a back-and-forth process that is incredibly luxurious. I would never expect it on any other project.”

The result is a game designed to suck players in by making you grow attached to the creatures that you help and interact with, as well as make players desperate to see how the story plays out.

Coker believes that anyone who plays through a dramatic moment at the end of the game’s first act will be motivated to finish the entire game. It’s an intense sequence that relies on the feelings you’ve developed for the characters over the last few hours, and it’s a moment that Coker is proud of.

“I’m obviously biased, but I think in 10 years’ time when I look back at it, I’ll still love it,” he said.

There’s a single musical moment that will probably stick in the players’ minds, but it works most effectively because of everything that comes before it — the mix of hope, dread, and camaraderie that has been building up from the moment the game started, all culminating into an agonizing climax.

“You have to pace things, and if the pacing doesn’t feel right, the emotion is not going to land correctly,” Coker said. “The end of act one is one of those things that we were able to pace really, really well, and I think it will hit for a lot of people.”

For anyone who enjoyed Ori and the Blind Forest, it comes as no surprise that its sequel plays your emotions like a fiddle. The heart-breaking prologue of the original game also conveyed a distinct pain and loss in its music, and it came from a very personal place.

“I had something pretty intense going on in my family at the time, so it hit pretty close to home for me,” Coker said. “I think other people, when they cry during the prologue — it is sad that they’re seeing Naru, but it’s probably linked to something that they’ve also experienced themselves.”

Living through a range of meaningful, impactful experiences is a valuable reference. It gives you some measure of insight as to whether a sound, a melody, or an instrument is effective at evoking something you’ve already been through.

“I think composers write better music when they’ve gotten out of their academic state and out of being in books,” said Coker. “I feel like my music has gotten better the more I’ve lived, and the more stuff I’ve done, and the more things I’ve experienced.”

For Ori and the Blind Forest, drawing on these experiences resulted in a soundtrack that won assorted accolades — though truth be told, he had no idea whether he had succeeded until the game was released.

“When I was doing Blind Forest, I felt like I was winging it. (It) may not sound like I was winging it, but I felt like it, because it was the first time I recorded a soundtrack of any length with an orchestra,” Coker said. “I’d done soundtracks before, but not with games with tight narratives like Ori and the Blind Forest has. You know, you just don’t know if people are going to like it.”

In the five years since Ori and the Blind Forest released, Coker has gained plenty of further experience composing music for games like ARK: Survival Evolved and Minecraft expansion packs. So returning back to Ori, Coker says he’s gained confidence in his ability to tell a story through music — something that reflects on Ori as a character, who has grown from being naive and young into a more experienced and mature creature.

“He’s grown up now, and I feel like I’ve kind of grown up as a composer, where I was like a kid playing around and kind of got lucky almost on the first one,” said Coker. “I feel like I’ve grown up with Ori in the process of doing these two games.”

But experience doesn’t mean that a fully fledged hours-long soundtrack will just take form in your mind. Getting it right takes experimentation, research, and seeking out inspiration.

“Listen to as much as possible, and listen to it actively — not just have it on in the background,” described Coker. “So many people now listen to music with it on in the background, with it on in the car, but active listening is sitting down and focusing on nothing else. No one has time for that anymore, so it’s quite hard to do, but I think it’s a really important part of the discipline.”

The more sounds that Coker exposes himself to, the more inspiration he has for new approaches to conveying a required mood.

For instance, in the track “Shadows of Mouldwood,” he tried to capture the idea of an unseen encroaching presence without having to rely on what he calls the “creepy horror strings” that you see in so many horror movies and games. His solution was to have multiple instruments play scratchy, irregular notes all from the same tonal scale, all scattered in different directions until they eventually converge and land at the same point.

“It sounds almost like a footstep,” he said. “You kind of don’t know where it’s coming from, and it’s like, ‘Oh! It’s there!’ And then it goes away. Then you hear it again and then it goes away. I start doing them really quietly, and over a minute period they get louder and louder. It’s not in sync with the gameplay. It’s more just like something is stalking you.”

Coker often tries to find ways to express feelings while making sure he doesn’t sound like anything that people have heard before. One approach he takes is to ask musicians he knows whether they have any unusual instruments that they think would work well for a particular melody.

For Ori, his main resource is Kristin Naigus, who owns hundreds of woodwind instruments, all of which she can play professionally. Naigus plays 20 different instruments in the soundtrack for Ori and the Will of the Wisps, including the mystical-sounding crystal flute and the deep, flurrying fujara. Naigus also convinced him to let her play a recorder, of all things, in the soundtrack.

“It’s actually an instrument I despise, but Kristin did such a wonderful job bringing this instrument to life in a way I could never have imagined,” Coker said. “I now like the recorder.”

Coker’s approach — his melding of the personal with the unfamiliar — has an odd effect on players. It transports them into an unfamiliar world, yet manages to dredge up their own personal experiences to create an intimate connection. It’s a moving journey that manages to feel all too familiar while still giving its audience a taste of something new.

By the end, Ori and the Will of the Wisps will make players feel something; that’s almost a guarantee — and the music is well-tailored to guide them along the way.

“I don’t want to tell people what to feel,” said Coker, “because people will experience different emotions when playing this game, but my hope is that people feel that the music helps them to take them to that place.”

Published: Mar 16, 2020 03:43 pm