This discussion and review contains spoilers for House of the Dragon episode 2, “The Rogue Prince,” on HBO.

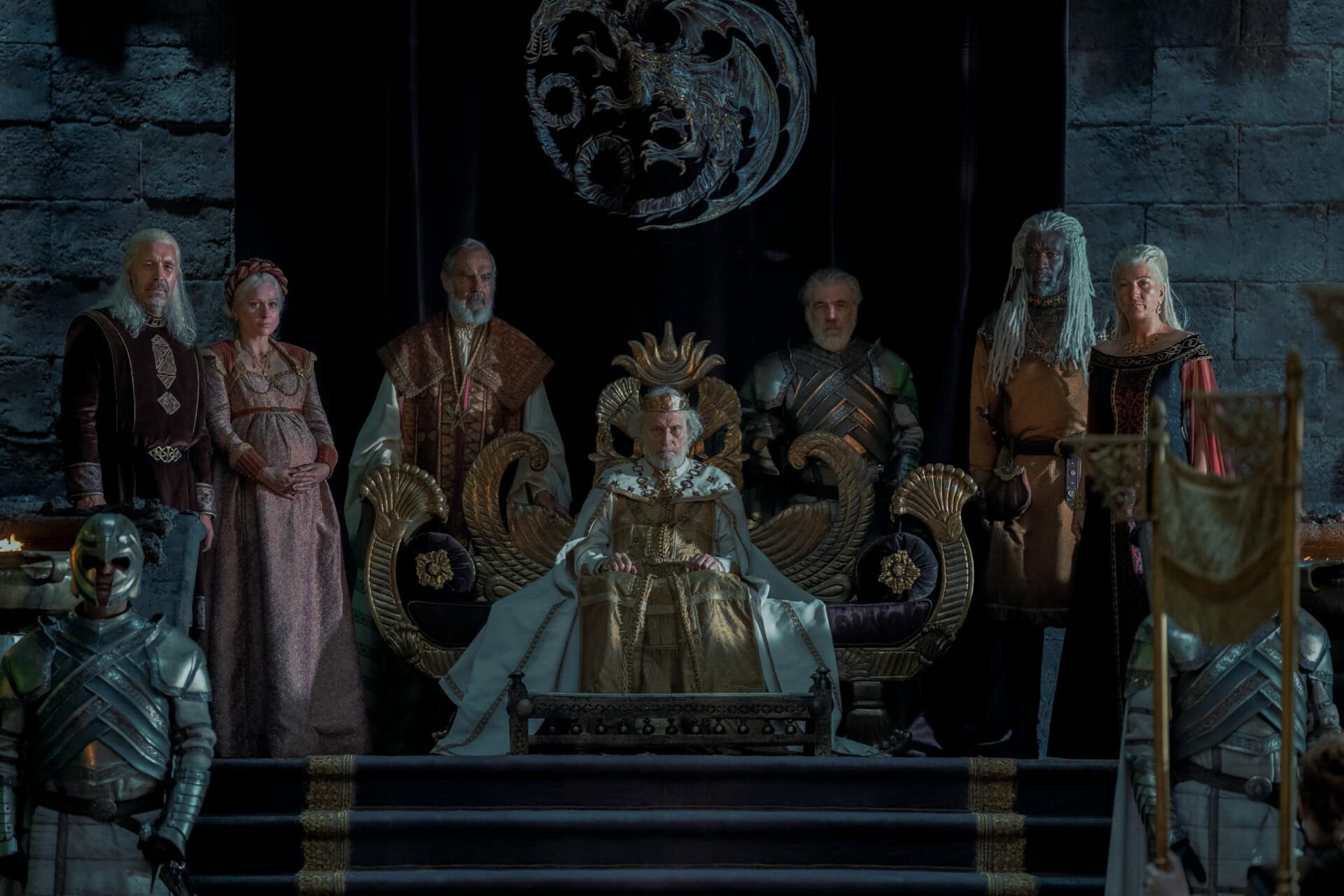

There are any number of obvious parallels that might be drawn between Game of Thrones and House of the Dragon. Indeed, it’s possible to draw direct analogues between characters. Otto Hightower (Rhys Ifans) gives definite Tywin Lannister (Charles Dance) vibes, and King Viserys (Paddy Considine) has certain echoes of Robert Baratheon (Mark Addy). There are also certain creative choices designed to reinforce the comparison, like the Tourney in “The Heirs of the Dragon.”

However, there are subtle but important differences. The Seven Kingdoms are in a very different place in House of the Dragon than they are in Game of Thrones. The first season of Game of Thrones takes place in a period of political instability in Westeros. House Baratheon are only 16 years into their reign following Robert’s Rebellion against the Mad King Aerys Targaryen (David Rintoul). This is part of the reason why “the game” is in full swing. Robert’s reign is precarious. The throne is in play.

In contrast, House of the Dragon takes place more than a century after the Targaryen conquest of Westeros. Viserys has ensured relative peace and prosperity for the continent. House of the Dragon pays remarkably little attention to the Great Houses of Westeros, and to the Seven Kingdoms themselves, because they are largely secure. While Viserys and Robert are largely defined as inattentive and indecisive leaders, the context around them is somewhat different.

There is a sense of restlessness at play in House of the Dragon. “It’s been seventy years since King Maegor’s end,” mused Rhaenys Targaryen (Eve Best) of the Tourney in “The Heirs of the Dragon.” “These knights are as green as summer grass. None have known real war.” Rhaenyra (Milly Alcock) makes the same point when choosing her father’s new bodyguard in “The Rogue Prince,” wondering, “How many of these knights have combat experience, beyond catching poachers?”

There’s a tradition that the health of a state can be determined by considering the wellbeing of its leader. Viserys’ health is degenerating from cuts he received sitting on the Iron Throne. (It literally is “the most dangerous seat in the realm.”) He has been sedentary for too long. Grand Maester Mellos (David Horovitch) tries to halt the spread of infection, assuring his king, “The maggots will remove the dead flesh and hopefully stop the advance of the rot.” If only it were so easy to heal a country.

“The Rogue Prince” returns time and again to the idea of rot and decay. The episode’s opening scene depicts the aftermath of a battle, rather than the battle itself. It focuses on the shipwreck and the bodies of the survivors tied to the shore in the hope that nature might claim them, so that the crabs should consume them. Maybe the crabs are just a more extreme example of the maggots being deployed to clean Viserys’ infection, to eat away the detritus.

Much of the drama of “The Rogue Prince” is built around the importance of dragon eggs to the Targaryen family, with Daemon (Matt Smith) stealing the egg that Viserys had intended for his dead son Baelon to provoke his brother. Daemon claims to want to present the egg to his own son, only for his new wife Mysaria (Sonoya Mizuno) to reveal that she has sterilized herself. “I ensured long ago that I would never be threatened by childbirth,” she explains.

With this in mind, it’s interesting that Viserys is the rare member of his family without a companion dragon. It’s a piece of symbolism that renders him almost as impotent as his inability to produce a male heir. Viserys was the last rider of Balerion, the dragon that Aegon the Conqueror rode when he brought Westeros to heel. As such, Viserys is the last indirect tether back to House Targaryen’s glory days back in Essos. It is no wonder he spends his days fixated on a scale model of Valyria.

There is a melancholy at play in “The Rogue Prince,” a sense Viserys finds more comfort looking backward rather than forward. Lord Corlys Velaryon (Steve Toussaint) suggests his daughter Laena (Nova Foueillis-Mose) as a match for Viserys, promising such a union would “show the realm that the Crown’s strongest days are ahead, not behind.” Viserys does not choose Laena, instead selecting Alicent Hightower (Emily Carey), who bonds with him discussing his model work.

Game of Thrones reflected America’s self-image through the lens of high fantasy. The show’s ruthless and cynical approach to politics resonated in an era where political discourse had become increasingly gamified and polarized. Many critics read Daenerys’ (Emilia Clarke) time in Slaver’s Bay as a metaphor for American intervention in countries like Iraq and Afghanistan. George R.R. Martin has stated that the Night King (Vladimir Furdik) was a stand-in for the threat of climate change.

As such, it’s hard not to read subtext into the portrayal of Viserys as a kindly but ineffective old man, who lacks the will for the kind of decisive action that is necessary to preserve the realm. Given House of the Dragon was written and filmed last year, it is intriguing that “The Rogue Prince” is built around a blonde narcissist who has committed “nothing less than sedition” by taking “a dangerous weapon” to his private residence against the rule of law, with the state having to retrieve it.

More broadly, Viserys is informed by a strong and melancholy nostalgia, one that perhaps resonates with contemporary America. “Do you believe Westeros can be another Valyria, Your Grace?” Alicent asks. Viserys considers the question. “That depends, whether you speak of the Freehold at its height or at its fall,” he replies. “The glory of old Valyria will never be seen again.” There is a sense of an idealized past that has been lost and cannot be recovered.

Towards the end of “The Heirs of the Dragon,” Viserys confessed to Rhaenys that he was haunted by a dream. Dreams are important to House Targaryen. After all, the family only survived the apocalyptic “Doom of Valyria” because Daenys the Dreamer had a prophetic dream that convinced her father to move the family’s seat of power to the Dragonstone. That vision — one tied to immigration, moving from Essos to Westeros — was what positioned the family to rule.

There is some small irony in the fact that the family dream that guides Viserys, the prophecy that Aegon had winkingly titled “the Song of Ice and Fire,” will inevitably end in ruin for House Targaryen and for Westeros. Daenerys will stop the White Walkers, but she will also bring death and destruction to the continent and the city. The audience understands that Viserys’ dream is more of a nightmare and that the path that he is trying to chart will inevitably lead to the collapse of his dynasty.

There is some interesting subtext here. Within the mythology of A Song of Ice and Fire, Valyria is perhaps most directly comparable to Rome. As such, Viserys’ nostalgia for Valyria as a lost ideal, and the question of whether Westeros can ever succeed it, recalls the fixation on America as a modern-day counterpart to Ancient Rome. That argument is quite common at times of social and political unease. It has been resurgent in recent years, as America grapples with its place in the world.

That said, there is one more rather pointed parallel between House Targaryen and American self-image. Game of Thrones has often compared dragons to nuclear weapons. Author George R.R. Martin has described dragons as the fantasy world’s “nuclear deterrent.” Daenerys’ attack on King’s Landing in “The Bells” was reminiscent of the nuclear attacks on civilian populations at the end of the Second World War.

Martin ties House Targaryen more explicitly to nuclear holocaust. Most theories about the Doom of Valyria suggest that the natural disaster was due to a massive volcanic event or a freak meteor strike. However, the depiction of the ruins of Old Valyria in “Kill the Boy” recalls the aftermath of a nuclear attack, even as Daenerys’ dragon Drogon flies overhead. Martin’s account of the City of Mantarys as “a place where the men are said to be born twisted and monstrous” also plays into this.

At the end of “The Heirs of the Dragon,” Viserys warned his daughter about the threat unleashed by the dragons. “The idea that we control the dragons is an illusion,” he confesses to Rhaenyra. “They’re a power man should never have trifled with, one that brought Valyria its Doom. If we don’t mind our own histories, it will do the same to us.” The doomsday clock is ticking. Given that House of the Dragon must inevitably build to the Death of Dragons, Viserys’ anxiety is understandable.

There is another subtext to this depiction of House Targaryen as an institution trapped in a slow decline that may swiftly accelerate. HBO has a lot riding on House of the Dragon. When the show was first commissioned, it was one of a slate of potential Game of Thrones spinoffs, but it was the only one to make it to air after a disastrous $30M pilot was canceled. Given the failure of the network’s efforts to find a successor to Game of Thrones, can House of the Dragon fill that void?

Indeed, the current volatility of the media landscape means that the cable provider has even more riding on the show than it did when it was commissioned. Reporting around the launch of House of the Dragon has a vaguely apocalyptic tone. Peter Kafka summarized House of the Dragon as “The Sequel to Game of Thrones That’s Really a Prequel But Whatever It Is, It’d Better Work.” The company appears to be feeling the pressure, pushing hard on marketing.

Given the unfolding chaos behind the scenes at Warner Bros., there could be a real-life Death of Dragons looming on the horizon. It’s hard to blame HBO for acting like Viserys — returning to a beloved model and wondering whether the past can ever be recaptured.

Published: Aug 28, 2022 10:00 pm