The sheer number of storytelling improvements in video games really stood out in the 2010s, ranging from the incremental to the truly innovative, facilitating better — and sometimes altogether new — ways for games to tell their tales. This trajectory of improvement makes even more sense when you consider the fact that “Narrative Designer” didn’t become a common standalone job description in game development before the mid-2000s. As the discipline has emerged, narrative design has changed, and it has gained much more respect and influence across development teams of all shapes and sizes.

Narrative design is inextricably linked to the gameplay it supports and the underlying technology that powers both, so the games that most impressed me with their storytelling methods often did so for very different reasons. My intent in this retrospective is to highlight some specific examples of narrative design, from 2009 to the present, and explain why they’ve left the largest impressions on me, both as a player and as a developer.

Virtual reality is an easy place to start. Since the first widely accepted headsets came to market in 2016, presenting experiences with unparallelled immersion has brought a lot of unexpected design challenges. Of everything I’ve played in VR to date, developer Ready at Dawn’s adventure game Lone Echo (2017) sets my personal high-water mark for VR storytelling and narrative design. In it, you play as an ECHO ONE, an advanced AI bot working alongside the captain of a deep space mining station near Saturn. Of course, things go awry.

Stunning visuals, zero-g traversal, and VR’s inherently immersive nature aside, Lone Echo uses some pretty slick mechanisms and design choices to help tell its story. The holographic interface that projects dialogue choices and messages is easy and fun to use, and on-screen text from UI to environmental art is clean and comfortably legible — no small task for early VR.

Virtual reality is also a lot more effective at telling stories using environment and props, and a lot of this seems tied to the sense of scale and presence that VR can convey. Players are typically willing to spend more time exploring rich virtual spaces than traditional pancake experiences, and Lone Echo understands this — the game can be completed in around four hours, but average playtime is between six and eight. From the get-go, there are tons of optional props to examine, each of which manages to do a tiny bit of extra world-building or character development. The game also proves that having a voiced player-protagonist in virtual reality can be very effective — still a relative rarity in the medium. The story itself is quite good as well, but what really elevates the whole experience is how Ready at Dawn has found those wonderful approaches to the challenges of delivering a powerful narrative in VR.

The past 10 years have also breathed new and exciting life into detective-based gameplay, unfolding mysteries in ways that require some actual creative thinking, and maybe even (gasp!) a little note-taking. Games like Her Story (2015) and Hypnospace Outlaw (2019) stand out in particular from a storytelling perspective because they don’t spoon-feed the player. They provide the player with a large database of story bits to peruse, like a database of short video clips (Her Story) or an alt-history version of the internet with a sci-fi flavor (Hypnospace Outlaw), and some basic tools to explore them. The storytelling in both is strong enough to serve as its own reward.

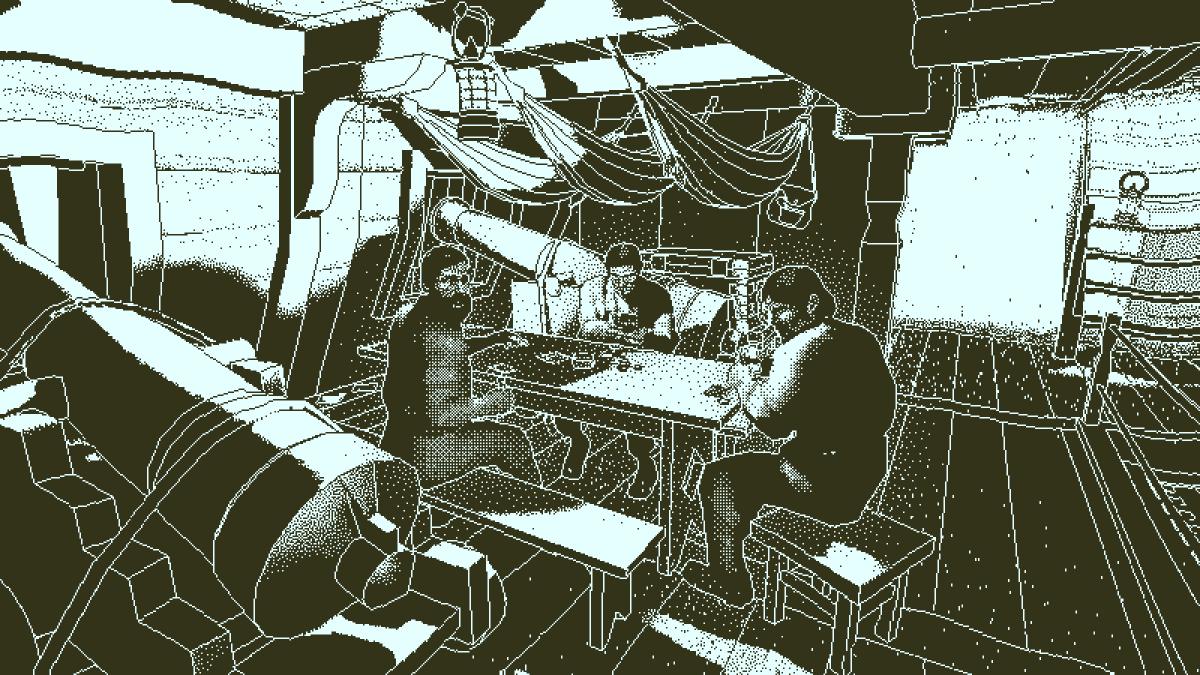

My absolute favorite detective game of the past decade takes an entirely different approach to narrative design, and it’s one of the most compelling and unique ways to experience a story. Developer Lucas Pope’s Return of the Obra Dinn (2018) puts players in the uncommon role of an insurance adjuster in 1807. The titular ship has returned to port with no one on board, and you’re tasked with uncovering the names and fates of its 60 crew and passengers with nothing more than your handy ledger and a pocket watch that has the ability to reveal frozen moments in time — each pertaining to someone’s death.

Each time you discover one of these moments, via a “one corpse leads to another” loop, it’s preceded by a short clip of voice-over that pertains to the scene you’re about to explore. By isolating the audio from the visuals for each fresh flashback, the game gently teaches players to listen for the finer details. Tiny details like different accents and references to character names and events must then be married with the visual cues present in the subsequent moment or cross-referenced with previous clues. Groups of clues are broken into chapters for easier parsing, but they unfold in reverse order. The end result of all of this is a masterclass in narrative design that will make you feel smart as you begin putting everything together.

Another fascinating narrative design development from the past decade is the rise of purely narrative-driven games set in 3D space. “Walking simulator” began as an intentionally reductive pejorative meant to deride games that focus on story to the exclusion of all other traditional notions of “gameplay.” It’s now part of the lexicon, though it’s probably about as useful as calling all FPS games “shooting galleries.”

Gone Home (2013) is the game that most folks use as a touchstone for the genre. Instead of writing being treated as the spackle applied to support other design considerations, story was the focus, with all other systems designed to support its delivery. Personally, I think that games like The Stanley Parable (2013), SOMA (2015), Firewatch (2016), and What Remains of Edith Finch (2017) are examples of these types of story-first games at their best because of the intimate relationship they forge between player and the story. Gone Home and Edith Finch have the protagonist’s narration, Firewatch and SOMA have engaging radio banter, and The Stanley Parable leverages a really clever type of dynamic narration based on player actions. It’s an incredibly effective tool when used dynamically, functioning similarly to that seen in Supergiant Games’ excellent isometric hack-and-slash adventure debut, Bastion (2011).

There are also some specific types of narrative design improvements and innovations from the past decade that were really clever in and of themselves. Episodic structure and “previously on” recaps pioneered by games like Alan Wake (2010) and basically all of the Telltale adventure games since The Walking Dead: Season One (2012) really help take the sting out of remembering where you are in long-form entertainment — especially when you’re not binging it.

And you can’t discuss revolutionary narrative design without mentioning Disco Elysium (2019), an impeccably written, thought-provoking CRPG. The fact that the game’s writing can be called “interactive literature” without hyperbole is beside the point. It’s not even that it has more content than you can see in three full playthroughs of about 35 hours each. It’s how the game creates that variety of experience by ostensibly turning each of your character stats into a character itself. The abilities you favor will not only affect your available paths through the story, but also affect your character’s internal monologue. This, in turn, affects how the burnt-out detective protagonist sees the world around him, and it flavors the overall experience in incredibly clever, funny, and thought-provoking ways.

One more aspect of improved narrative design that I’ve loved as a player this decade is AI-controlled companion characters and how they have become more believable. In games like God of War (2018), Red Dead Redemption 2 (2018), A Plague Tale: Innocence (2019), or basically anything Naughty Dog developed the past decade, you spend a lot of time accompanied by an NPC. Presentational improvements increasingly enable player-character relationships to support additional nuance. You end up learning and caring more about the characters themselves and get some extra world-building and storytelling to boot.

It’s no coincidence that I find myself feeling like I know Ellie and Joel, Kratos and Atreus, Amicia and Hugo, or Arthur and literally all 24 members of the Van der Linde gang. And to be honest, this and the other evolutions described all have me incredibly excited about the interactive stories of the coming decade and the compelling new ways they’ll be told.

Published: Dec 29, 2019 7:00 PM UTC