It appears that April is no time for No Time to Die.

Earlier in the week, Universal announced that they would be moving the release of No Time to Die from April to November, due to concerns about the spread of COVID-19. There has already been a little bit of release date chess, with Universal moving Trolls World Tour up to April 10 to replace No Time to Die and STX pushing My Spy back to April 17 to take the slot vacated by Trolls World Tour.

It is estimated that COVID-19 has already cost the film industry over $5B. Nearly 70,000 cinemas in China are closed. AMC shut down 22 locations in Italy. SXSW is canceled. There are questions about whether Cannes will go ahead. The Met reports cinemas in Switzerland and Japan canceling event screenings. Film production has halted in China. Mission: Impossible 7 stopped filming in Venice.

No Time to Die was the first major film to have its release plans altered to account for the coronavirus. It will not be the last. Mulan is a possible candidate. While Disney insists that Black Widow will release on May 1, it would also appear to be in jeopardy. Depending on how long the health crisis lasts, the same may be true of F9 and Wonder Woman 1984.

This crisis reveals a lot about the state of the modern film industry. In particular, the No Time to Die delay demonstrates how tightly connected the modern world is in terms of film production and distribution. After all, while the number of coronavirus cases continues to increase in both Europe and North America, a major impetus for these delays is the importance of Asia as a market for modern blockbusters.

The 21st century has seen the global box office grow in importance. In 2000, the international box office accounted for only 51% of the market. By 2019, it accounted for nearly three-quarters. The domestic returns actually shrunk by 4% last year. (Notably the success of Avengers: Endgame was driven by China. It is only the second highest-grossing film ever at the domestic box office.)

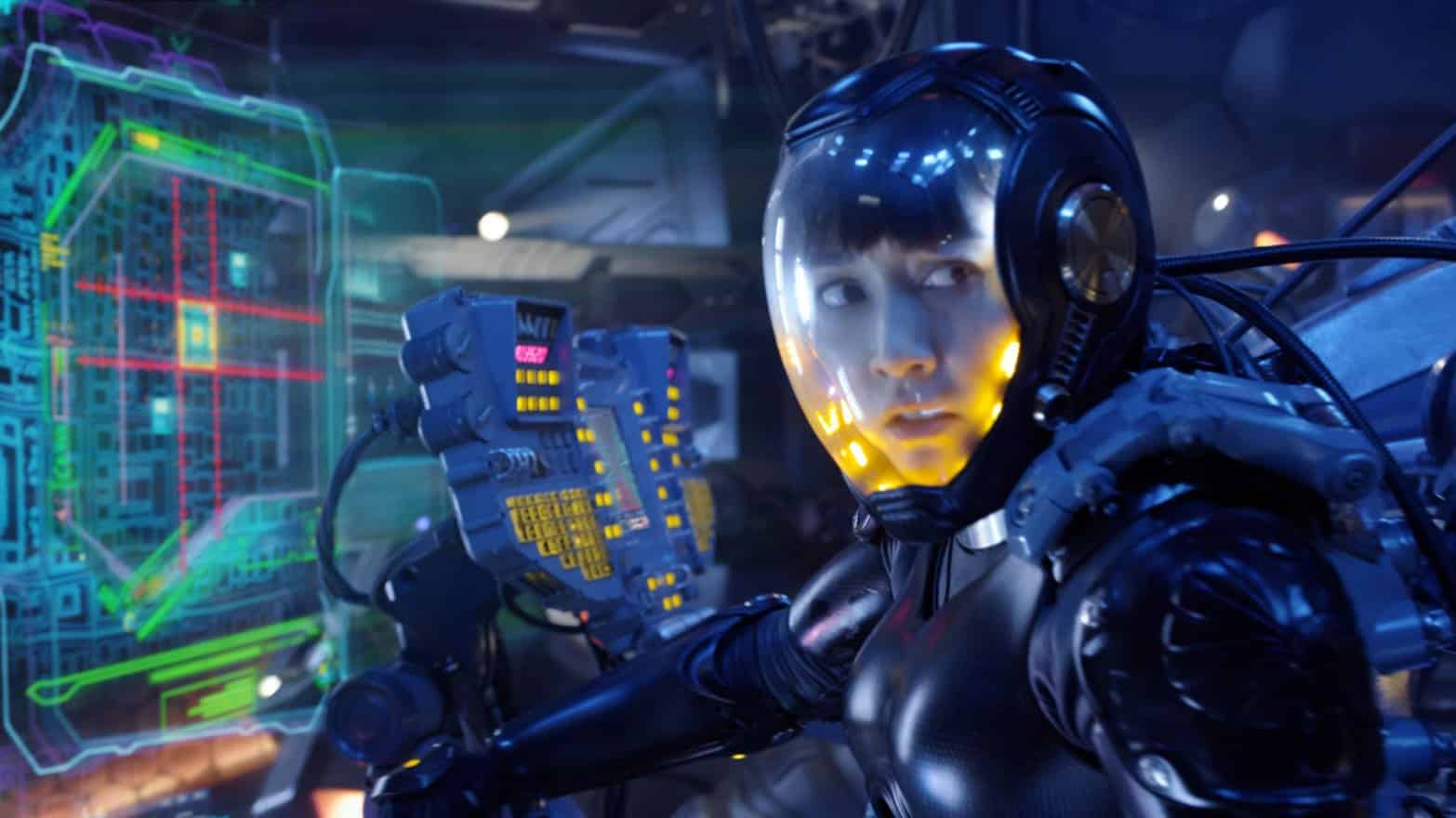

In 1999, the Chinese box office was worth $200M. Twenty years later it is worth over $9B. It became the world’s second-largest film market in 2013. The Chinese market is increasingly important to Hollywood, even if it remains unclear how important Hollywood is to it. China can make or break films. Pacific Rim flopped domestically, but it earned enough in China to justify a sequel.

China is a large part of the equation, but it is not the only factor in play. Japan is the third-largest film market in the world. It has grown by almost two-thirds since 2000. Last year, foreign films made $1.1B at the Japanese box office. India is the fourth largest, with Hollywood beginning to break into the local film market.

The past decade has seen Hollywood becoming increasingly cognizant of these markets. China has begun to dictate narrative choices, as major studios alter film plots to make their films more palatable to the region. Iron Man 3 included an exclusive-to-China subplot in which a new character played by Wang Xueqi scolds Tony for his hedonism and later performs surgery on the Avenger.

American box office stars are more likely to be exported, in an effort to create a bridge between the two markets. Matt Damon and Christian Bale have both been drafted into high-profile Chinese productions. It isn’t even just big-budget theatrical releases. Sylvester Stallone produced his first direct-to-video Escape Plan sequel with Chinese company Leomus Pictures.

As a result, blockbusters have become increasingly internationalized. This is obvious with things as simple as release date shifts. In 1996, Independence Day waited over a month between its American and British release dates. In 2016, Independence Day: Resurgence released in over 40 markets (including China) within the space of three days.

These days, major films have day-and-date releases worldwide in order to minimize the risk of spoilers and piracy. While occasionally films like Parasite and Dark Waters will take months to roll out internationally, even seemingly smaller films like Little Women or Knives Out will try to keep their global release dates relatively synchronized. (Knives Out played very well in China.)

To pick one example of a movie that is very much at risk, Mulan demonstrates the importance of China to companies like Disney. The original film wasn’t a huge box office performer in the context of the Disney Renaissance, earning less than The Hunchback of Notre Dame. However, Disney has invested heavily in it, reportedly affording it the largest budget of any of the live-action remakes.

The success of the live-action Mulan is more dependent on China than on the United States. The synchronized global release date is a large part of that. The 1998 animated movie underperformed in China because the government delayed its release in response to Buena Vista’s distribution of Kundun. By the time the animated film was released in China, it was already widely pirated.

Even the James Bond movies demonstrate the extent to which modern blockbuster cinema has become a global proposition. Casino Royale earned about 18% of its total box office returns from the United Kingdom alone, and another 28% from the United States. By the time that Spectre was released, 14% of revenue came from the United Kingdom and 22% from the United States.

The Bond movies themselves demonstrate this shifting reality in narrative terms. Historically, the Bond movies have been about presenting exotic foreign locales to British and American audiences: Jamaica in Dr. No, Turkey in From Russia with Love, Greece in The Spy Who Loved Me. The presumed audience was British, with America itself occasionally exoticized, like in Goldfinger, Live and Let Die, and A View to a Kill.

It is notable that both Spyfall and Spectre made a point to invert the format. These films featured major set pieces built around the United Kingdom itself – the Underground attack and Scottish manor in Skyfall or the climactic confrontation on the Thames in Spectre. The series had set sequences in Britain before – such as the opening to The World Is Not Enough – but not as many and so densely.

There is a clear sense in which Spyfall and Spectre are designed to package British iconography for foreign audiences, to make Britain itself seem like an exotic locale in which James Bond operates. It suggests that the assumed audience of these films has changed, that the viewers watching Skyfall are as likely to be impressed by Churchill’s bunker under London as a neon casino in Macau.

To be fair, local film industries are still thriving. While Parasite director Bong Joon Ho might argue for his film’s international appeal by suggesting that “we all live in the same country now: that of capitalism,” the film is still firmly anchored in a South Korean context, down to allusions to Taiwanese cake shops. Knives Out might play well internationally, but it is about America.

The coronavirus will have a profound impact, but the speed at which it has spread serves as an illustration of how densely and tightly interwoven we are in this modern globalized age. That is as true of cinema as anything else.

Published: Mar 9, 2020 11:00 am