Pathologic 2 didn’t get a lot of attention when it released last year. There were good reasons for that: It is a follow-up to a game that was notorious for its poor Russian-to-English localization, it ran badly, and it was exceptionally — arguably unfairly — difficult. It did have an excellent English localization this time around, and developer Ice-Pick Lodge introduced a slew of patches and difficulty sliders to tweak all aspects of the gameplay in the weeks following its release, but it was too late. The game had missed its opportunity to make a positive impression on the mainstream press, and it was relegated to cult status within just a few months of release.

Part of me thinks that’s just fine, since Pathologic 2 is absolutely not for everyone, but I also believe it deserves much more recognition than it got. Because once you turn the difficulty down (I don’t advise this often, but turn it all the way down.) and get over the uneven performance, you are left with a singularly fascinating experiment in what I’m going to call “method role-playing.”

To understand what I mean here, consider a typical role-playing game like Baldur’s Gate or The Witcher. In the former you build a character out of a set of variable characteristics and then pretend-play as that character for the rest of the game. In the latter you assume an existing, predetermined role and do the same. In both you make dialogue choices and decisions that affect the progress and usually the ending of the story, broken up by bits of gameplay that itself offers more or less player choice.

However, you do not need to pay a huge amount of attention to the story in either type of game. It is possible to ignore most cutscenes, or click through most dialogue options and decisions, and still make it through to the end.

That is not the case with Pathologic 2. Not every dialogue choice or decision will progress the story in a particular direction, and if you dawdle too long or make too many disparate and unconnected choices, you will eventually face the so-called “Late Ending”: an unsatisfying conclusion that effectively mocks you for not paying enough attention and not doing anything of real substance.

To get the intended experience from Pathologic 2, you have to go beyond the pretend play of traditional RPGs and learn the role you are given (something the game heavily implies with a meta-narrative set inside a theater). That means paying attention to every piece of information you are presented with — every bit of the local dialect, history, customs, and opinions — and internalizing it until you can speak, think, and apply it back to the game world to form your own view of that world. By analogy with method acting, Pathologic 2 requires you to method role-play: to inhabit the game’s protagonist and their environment.

This is not an easy thing to do. Pathologic 2 is set in The Town, a turn-of-the-20th-century province in an unnamed country that is a bizarre mix of architectural styles, technologies, customs, and characters. You play as Artemy Burakh, a Haruspex, a term that seems to be loosely borrowed from ancient Rome to describe a quasi-religious official who studies the interconnections between the physical and the spiritual. Artemy had left The Town to study medicine in a big city and is recalled years later by a letter from his father, a well-respected local physician. On arrival, Artemy finds himself a stranger in his birthplace, overshadowed by his father’s achievements, and expected to follow in his footsteps.

This is already a lot to take in, and while Pathologic 2 does give you a few hours to do that, eventually The Town becomes infected with a deadly plague, its citizens start falling ill and dying, and you have just 12 days (Each one takes about two real-life hours.) to understand what caused it and how to stop it.

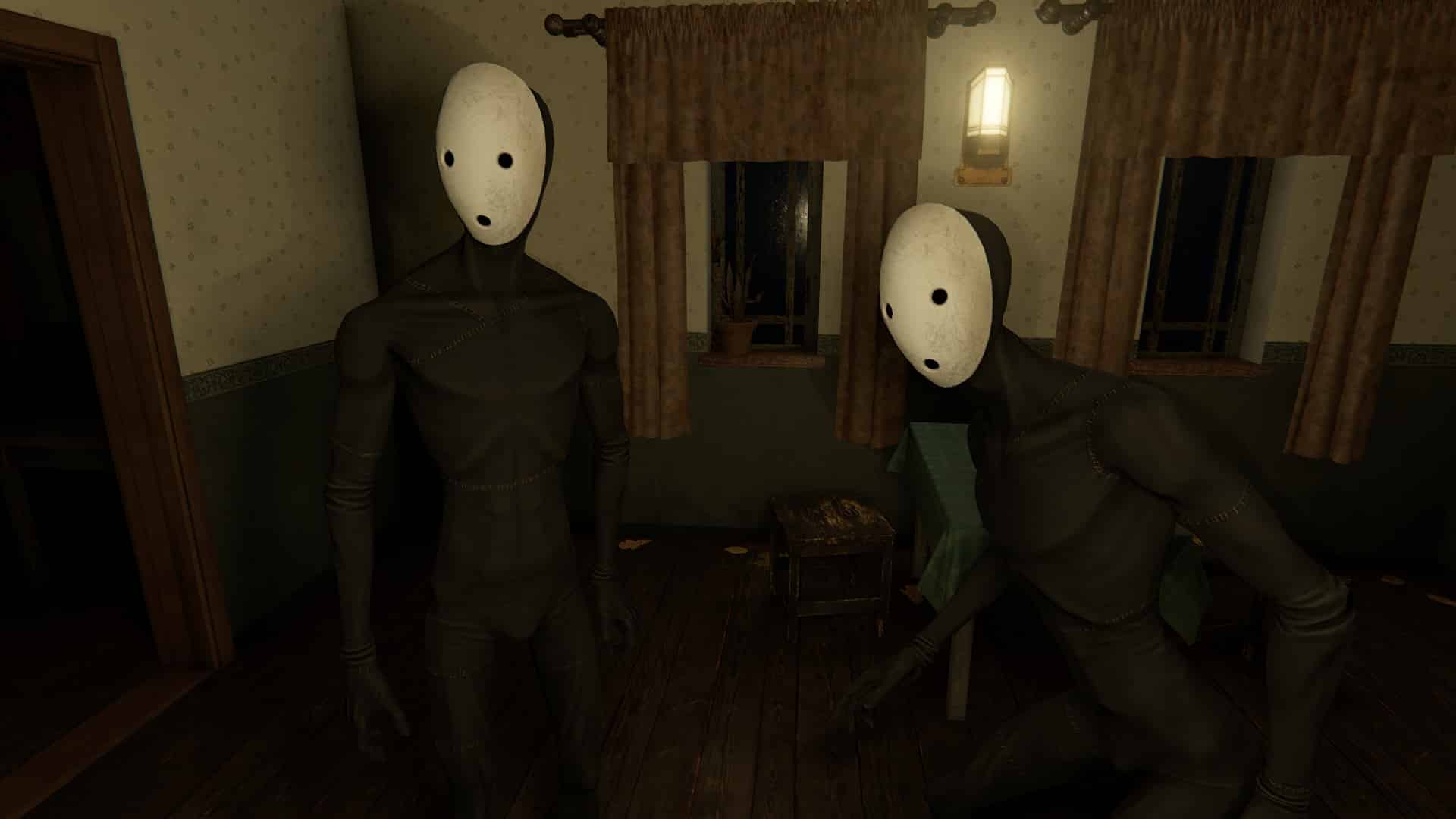

It is impossible to heal — or even visit and speak to — everyone who falls ill in a given day. It is likewise impossible to pursue every story thread or bit of lore, especially since many characters give contradictory information, seem to outright lie, or may even be figments of Artemy’s imagination. For example, late in the game the plague begins manifesting itself to Artemy as a plague doctor.

You get thirsty, hungry, tired, and can become infected or injured in combat. You also need to monitor your immunity, inventory, and supplies. If you don’t do this and push yourself to try to complete everything in a given day, you will wear yourself out and eventually die. Or you will run out of resources and get stuck in a loop of trial and failure that’s difficult to solve by loading earlier saves, since many decisions don’t have follow-on consequences until hours later.

There is no glossary or codex and no objective marker to keep you on track. Despite this, you need to learn your Shabnak-Adyr from your Bos Turokh, your Boddhos from your herd brides, Erdems from Bohirs, and many other pieces of lore and tradition, or you will say the wrong things to the wrong people and shut off possible avenues for progression. And if you do not decide which approach to the plague and to The Town’s general future you agree with — from the scientific rationalism of the big city to the mysticism of the local steppes tribes — you will lose your thread on the main story entirely.

If you can internalize all that and make peace with it, then you’ll find you are method role-playing as Artemy. You’ll realize it’s not possible for Artemy to complete every task, save everyone, or share his viewpoint with them, so equally it’s not possible for you. You’ll embrace the fact that quests will go uncompleted, NPCs will go unspoken to, and large aspects of the story will remain unknown, and you’ll just play according to your chosen style and perspective on The Town.

I found it stressful at first — completionist habits die hard — but it makes room for the punishing systems, bleak story, strange setting, and rich lore to come together in one of the most unique, thematically ambitious, and rewarding narrative experiences in recent memory.

Published: Nov 4, 2020 11:00 am