I went into a random suburban house in Redfall and ended up in a crime scene.

The house didn’t look like much, but the front door was unlocked, which I took as an implicit announcement there was something inside. Instead, the first thing I found was a smartphone on the kitchen table. The woman who lived here, Ramona, had been texting her sister about their plan to ambush their mom and stepfather.

Upstairs, behind a locked door, I found the site where they’d done it, with a bloodstained tarp across the floor. Ramona had warned her sister that their stepfather was an ex-boxer, so he’d be hard to take down — but there was nothing there to tell me who’d won that fight. It was just blood, and no bodies, in an abandoned house, with no answers or ending.

In practice, this is just set dressing. It probably shouldn’t have stuck with me as hard as it did, particularly in a game that’s ostensibly about vampire gods who can push back oceans. When I think of the time I’ve spent on Redfall, though, what’s stuck with me are the smaller, lower-stakes scenes like this.

When Redfall starts, it’s at the loudest, most violent point in its overall narrative. Vampires are real, they’re extremely powerful, and because they’re a little annoyed with you specifically, they just turned off the sun. Now they’ve got absolute control over the town of Redfall.

You play as one of the only four people left who’re fighting back on behalf of the surviving civilians, against crazed cultists, a corporate conspiracy, some vampire cannon fodder, and a black-ops kill team that’s fielded more gunmen than the invasion of Normandy.

Going into Redfall, though, I already knew I was going to push the game’s main storyline off for as long as possible. I spent a lot of Arkane Studios’ previous games playing amateur detective, digging through side areas, locked rooms, and random documents to find whatever side stories I could. I probably could’ve finished Prey in half the time if I didn’t get weirdly invested in trying to figure out what had happened to every single crewman on the personnel roster.

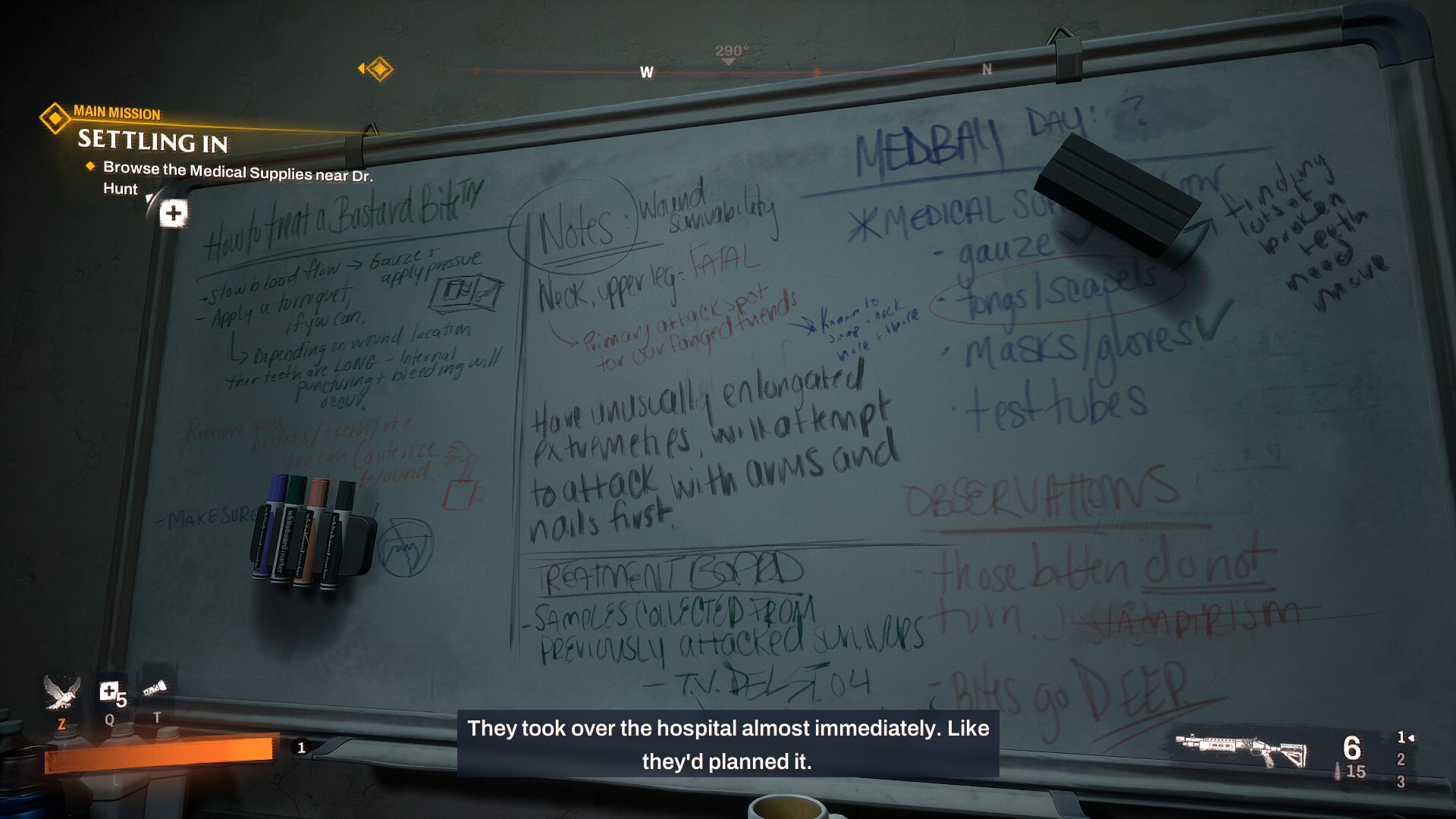

Once I had the chance to explore Redfall, what got my attention was the story, told piecemeal through diaries, newspapers, flyers, and environmental set pieces, of how the town used to be and how it reacted to the vampires’ initial attack.

Redfall got hit with a quick downward spiral that started with a couple of brutal murders, progressed into half the town going missing, and culminated in the other half of the town turning on itself. Most of Redfall went from planning weddings and preparing for autumn festivals to being hunted through the streets in the course of what couldn’t have been more than a couple of weeks.

I spent a lot of my childhood in waterfront tourist-trap towns like Redfall, and Arkane’s really nailed that weird, pleasant, inoffensive aesthetic. It gets a lot of visual mileage out of contrasting that everyday Americana with horrifying details: slicks of blood, paranoid ramblings, smirking vampires perched atop farmer’s market stalls.

The cults, in a weird way, are the scariest part of the game. The vampires are actually monsters and revel in it, but the cultists are written and act like they’re just people, complete with the occasional appalling New England accent.

The cults, we’re told, started from a handful of people who were particularly vulnerable to the vampires’ influence for one reason or another. By the time Redfall starts, some of the cultists have joined out of sheer desperate pragmatism, (What’re you gonna do, fight the guys who just turned off the sun?) but others are new addicts, turned into remorseless killers who just want another fix of the vampires’ blood.

The entry fee for joining one of the cults, we learn early on, is to bring in someone else as a sacrifice to the vampires. It doesn’t matter who. You can overhear conversations between cultists where they talk about whom they traded for membership and why, like old enemies from grade school or bosses they hated, but others betrayed their closest family member. It’s probably what Ramona and her sister had planned for their mom.

By the time the game starts, the remaining cultists have turned on each other, fighting over the handful of people who’re left, in the hopes that more sacrifices might mean they can get more out of the vampires they’ve chosen to serve. At the same time, the vampires that roam loose on the island are all thrill killers, content to attack whomever they see, while all the vampire gods have gone dark. Sure, they talk constantly — the background noise of Redfall Commons is the Hollow Man, raving from every nearby TV and radio — but they don’t do anything.

The cults are left in the position of trying to appease gods who clearly don’t notice them. By the time you’re about halfway through the game, it’s driven most of the cultists the rest of the way around the bend.

This isn’t to argue that the version of Redfall that you actually play right now is a secret masterpiece. As a game, it’s a bit of a mess. You can wring some fun out of it in multiplayer, but as a solo game, it’s an absolute drag.

What I’m going to take away from Redfall is that sense of slow-mounting, crazy paranoia, against the background of this weird, self-consciously pleasant small town. Redfall is the sort of American town that people spend their entire lives trying to escape from; Redfall is a game about forces that actively make it impossible. There’s another story in this, and maybe another genre of game, that I’d genuinely want to see.

Published: May 6, 2023 12:00 pm