As one of the biggest and most recognizable brands in the real-time strategy space, the Command & Conquer franchise played a pivotal role in building popularity for the genre that has sadly waned over the last several years. The now defunct Westwood Studios became a household name after the 1992 release of Dune II. The first Command & Conquer launched to critical and fan acclaim on DOS in 1995 and Windows 95 the following year. GameSpot’s review called it “one of the finest, most brilliantly-designed computer games” ever seen.

Westwood released a spinoff called Command & Conquer: Red Alert and expansions in 1996, 1997, and 1998 respectively that were just as well-received as the first game. That success turned Westwood into an industry darling and strategy juggernaut.

The Red Alert disc included a teaser for an entirely new game — Command & Conquer: Tiberian Sun, the sequel to the original Command & Conquer and one of my favorite strategy games of all time. Following a troubled development and multiple delays, Tiberian Sun finally shipped 20 years ago on Aug. 27, 1999 and was lauded by both critics and fans. It was a financial success, selling over 2.4 million copies before Command & Conquer: Red Alert 2‘s release in October 2000.

Tiberian Sun moved the series to a more 3D-style isometric viewpoint as opposed to the straight-up horizontal and vertical lines of the first two games. It oozed atmosphere thanks to the addition of lightning storms and other weather phenomena, day and night cycles, and even meteor showers. It became a blueprint for the rest of the series. Units could be queued up in bunches rather than one at a time. Hotkeys could be used for quick commands, and units were given veteran status based on the number of enemy combatants they killed. It all made for some thrilling improvements to the series.

Tiberian Sun was also brutally difficult. While Command & Conquer and Red Alert were no slouches in the challenge department, Tiberian Sun’s unique units meant foregoing a bull rush of dozens of mammoth tanks at once. Many units such as the Juggernaut artillery required an additional “deploy” input to actually transform into artillery and be used. Attacks required finesse and on-the-fly tactics to avoid being obliterated in mere seconds. That still happened a lot. (Damn you, flame tanks.)

Campaign missions were novel compared to Command & Conquer and Red Alert. The newer engine allowed for some fun scenarios like defending a downed UFO or initiating a prison breakout. Poisonous Tiberium… umm… plants could litter the map in certain areas, making them difficult to navigate. Alien-looking underground holes secreted deadly gases when shot, mutating your army into crazy monsters if they got too close.

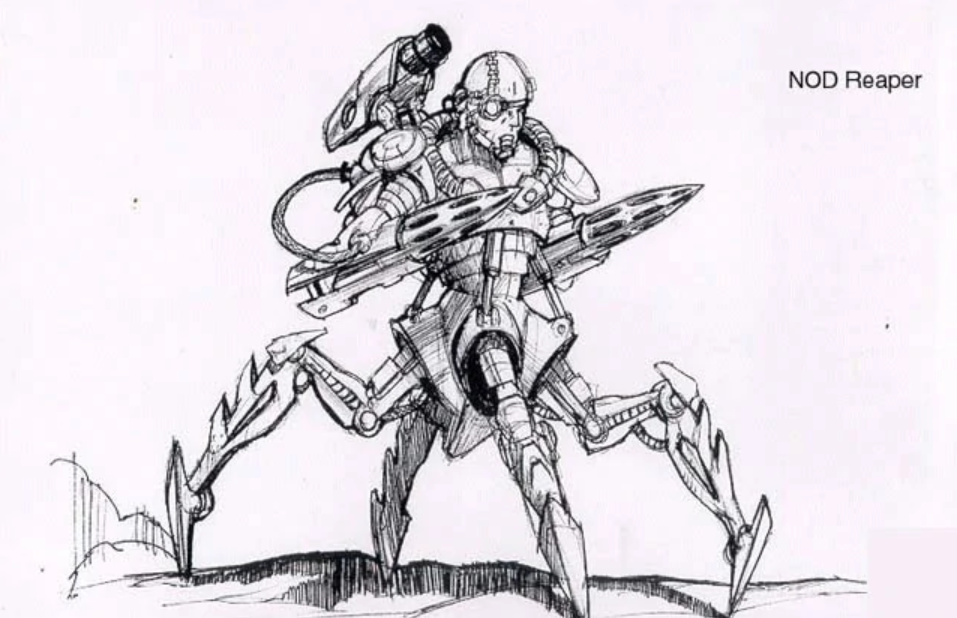

I poured ungodly hours into it on my trusty Pentium III. From the GDI Juggernaut to NOD’s terrifying Cyborg Reaper, Tiberian Sun‘s units were so unique in design and function that each campaign mission and multiplayer match felt excitingly fresh. The newly destructible terrain created self-inflicted obstacles. Performances from Michael Biehn (Aliens and The Terminator) and series veteran Joseph D. Kucan were simultaneously cheesy and endearing, helping to deliver a personal and intriguing story line.

Cyborg Reaper – Firestorm Expansion (FANDOM)

The team at Westwood spent an exorbitant amount of time revamping the franchise’s technology. The move to a more-3D look resulted in programming efforts taking over 10 times longer than originally estimated. Everything from terrain deformation to improvements in unit pathfinding played a role in making Command & Conquer: Tiberian Sun one of the studio’s most difficult projects.

Adam Isgreen Recalls the Challenges of Building Tiberian Sun

I recently had the distinct pleasure of chatting with Adam Isgreen, the former design director at Westwood Studios. A 25-year veteran of the industry now working on Age of Empires IV as a creative director at Microsoft, Adam’s career as a designer covered every game in the Command & Conquer series until Westwood’s closure in 2003. It was such a joy to reminisce about the good old days of one of the most prestigious franchises in the RTS space.

“I remember Louis Castle (Westwood co-founder) drawing on a whiteboard as he was talking about how we could use voxels to save a lot of memory and still get 3D units without making them truly 3D,” Isgreen said. “There were a lot of interesting elements in Tiberian Sun that we tried because we wanted to push on what hadn’t been done before in RTS. There was a lot of ambitious tech in the game — voxels, pathfinding, deformable terrain — and it was a new engine — so it can be hard to estimate time correctly when there’s that many new pieces.”

That technology push was instrumental in creating what ended up being both a strategy classic as well as a headache for the team.

“Deformable terrain was a big one,” Isgreen said. “We spent a good deal of time on the technology. I don’t think we had it 100 percent balanced by the time we launched it. We remedied it with concrete in (the expansion pack) Firestorm, but it ended up being almost unused in Red Alert 2 (which also used the engine) because you’d have to create the entire game around using or neutralizing that aspect of the game.”

Isgreen said one of the most difficult feats to pull off was the implementation of destructible bridges. “I don’t think many non-developers can appreciate just how hard pathfinding can be. Tiberian Sun had over/under bridges and tunnels with accurate pathfinding and it all worked as the player expected. That meant 10 times the pathfinding work by the engineers to deliver on that expectation.”

GDI Titans cross a bridge.

The combination of deforming terrain, destructible bridges, and unit pathfinding made Tiberian Sun feel unique compared to its predecessors. Rather than standard 2D planes, environments had far more detail resulting in more thoughtfully crafted maps. “I’m really blown away by what the team pulled off in the end, because that was not an easy thing to tackle,” Isgreen said.

Following up on darlings like Command & Conquer and Red Alert was a daunting task for Isgreen and the rest of his team. Players expected Tiberian Sun to deliver, and pressure was mounting prior to launch. Westwood Studios wanted their next game to entertain fans as much as they had in the past.

“There’s always pressure, but as a follow up to Command & Conquer and Red Alert, there’s of course additional pressure,” Isgreen said. “I don’t think we, and really I’m pointing the finger at myself here more than anyone else, got the balance right on deformable terrain. That’s more from the design side. I wish we’d had more time to iterate on its uses and play. Like all Westwood titles, we just wanted people to be excited to come back to the Tiberian world. A lot of very creative and technical people poured a lot of years into that game and you want to make people happy when you put that much of yourself into any piece of work. Westwood Studios was always about delight and emotional response. If you felt something while playing, that’s what made us happy.”

The enigmatic Kane watches over an execution.

The Quality That Separates Command & Conquer from Other RTS Classics

Sandwiched in-between StarCraft and Age of Empires II, Tiberian Sun faced stiff competition from other RTS heavy hitters. I always felt that Command & Conquer held its own against the rest with that something special to give the series its flair. Isgreen agreed, reflecting on the franchise’s love of the theatrical.

“There’s a lot of difference in the three ‘holy trinity’ RTS series as I call them,” Isgreen said. “For the Command & Conquer games, I think it’s that while we’d never be as balanced as the StarCraft/Warcraft games, we’d deliver more emotional swings and moments of bliss and panic than you’d find in any other real-time strategy game. Think of things like Tanya laughing or hearing ‘Kirov reporting’ when you’re playing allies in Red Alert 2 — totally game-changing on a psychological level! We lived for that stuff.”

We both recalled the intense panic that came from hearing an enemy weather device or nuke come online.

“That was the fun of it — the tension of knowing or not knowing that you have to change your plans,” Isgreen said. “It’s piling on more plates to spin. I always really appreciated what each game did differently, but the combination of massive faction personality, especially with Kane, and emotional swing, and ‘I feel like I’m cheating!’ units was always something that resonated highly with me.”

Tiberian Sun‘s Ion Cannon in action

The Legacy of Westwood Studios

Isgreen said Westwood Studios felt like a real family. The studio’s closure came as a gut punch for me as a lifelong fan. If it was that hard for me, I couldn’t imagine how it felt for a team member. I asked Isgreen if he still stays in touch with his former peers.

“I ran into a few at Gamescom, actually,” he said. “I chat with the Petroglyph team on occasion. I need to catch up with them. It’s been too long. Honestly, if Westwood hadn’t been shut down, I don’t think I would have left unless they got rid of me. It was this amazing group of highly passionate, artistic, and technical people that, while we’d clash on occasion, could produce some really great products. I certainly miss them. But I take all that learning forward and try to project that spirit of Westwood into everything I do now.”

It has now been 20 years since Command & Conquer: Tiberian Sun officially released in the United States. While Westwood Studios is no more, its legacy lives on through the hundreds of developers and creators that called the studio their home decades ago. Many continue to make their mark on the industry from inside Microsoft, EA, and other studios. Petroglyph Games, which is composed of many former Westwood employees, is currently hard at work remastering Command & Conquer, Red Alert, and all of the series’s expansions for modern PC systems.

Tiberian Sun and the rest of Westwood’s incredible portfolio of award-winning games really do stay with me to this day. Its campy FMV scenes and totally rad soundtrack delighted me as a player, and it’s an experience I’ll honestly never forget. Isgreen won’t either.

“My fondest memories of Westwood will always be the people — the smiles and shouts and laughs and love that everyone who worked there shared with each other. I came to Westwood as a green, arrogant designer who hadn’t had a lot of people challenging me to do better. Personally, Westwood made me do that in spades. I grew. And I think that’s the best compliment I can give to the place and the people that pushed me. I came out of it a much better person and a better designer. And I take that spirit forward now with everyone I work with. While Westwood may not be around any longer, its spirit is propagated in all the people that worked there. I intend to uphold my part in ensuring that spirit never dies.”

Published: Aug 27, 2019 6:30 PM UTC