There are some great examples of postmodernist self-awareness in video games. Too often, though, the attempts at cleverness fall short. The self-awareness fails to support anything in the story beyond itself, or jokes are made to make us apologists for shortcomings. Some might argue that such criticisms are invalid – that those traits are the direct result of a clear directorial vision – but that feels like an excuse to not take full advantage of the creative toolkit.

I’m in mind of this because of The Good Life, Swery’s recent absurdist slice-of-life RPG. It’s a curious little game where, as a photojournalist, you’re tasked with uncovering the secrets of “the happiest town in the world.” Through the game adventure, self-awareness manifests on two levels. The first level is an occasional metacommentary on the constructedness of reality: What we think of as real is dependent entirely on the way the subject is framed. It’s the kind of deep, thoughtful theme that, in other contexts, could very easily make the game a critical darling.

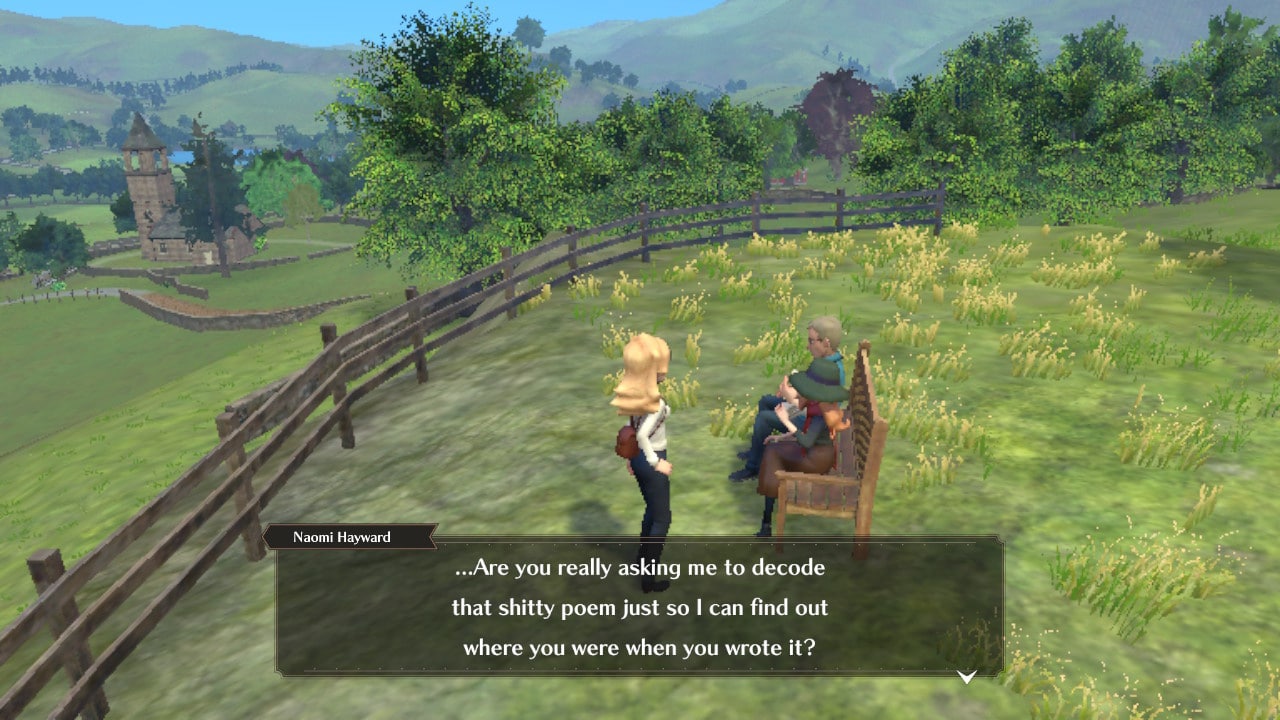

However, The Good Life doesn’t holistically grapple with that theme in the game because the second layer of self-awareness cuts through it. The Good Life wants you to know that it knows it’s a game. The dialogue draws attention to that fact, with protagonist Naomi commenting that her tasks in Rainy Woods are just like in an RPG, that she can overcome obstacles with game logic, and that she feels like she’s just watching things unfold through a screen. The nudges are directed at you to make sure you’re in on the joke, but they don’t work. They’re cheap gags – not funny and not fitting to the contexts they appear in. Worse, they draw attention to the fact that The Good Life relies entirely on reheated RPG quest structures and nonsense, failing to make you forgive the game for being so stodgily uninspired.

I might be more forgiving of these foibles if it didn’t all feel so damn familiar. The postmodernist edge was much more blatant in 2014’s Sunset Overdrive, and it exhausted the mine for those would-be-clever acknowledgements of the player’s role. That game succeeded in taking full advantage of knowing what it is. The gameplay involves you wholly with its focus on unrelenting momentum. It also leans hard into the inherent absurdism of video games by embedding tropes like respawns and invisible walls into the story.

However, Sunset Overdrive also fails in the same way as The Good Life, in that Sunset’s self-awareness detracts from the external narrative theme about the evils of indifference. Chiefly, the game is so busy stuffing its corporate apocalypse narrative full of “clever” jokes that it ultimately overlooks the harm done to individuals.

Sure, the video game industry was a little different back in the early 2010s, and we didn’t know so much about the discrimination that burbles under the surface. However, we had already known by then the damage that corporate indifference can do. And in 2021, just as we find out that Activision Blizzard is still dragging its feet on action to improve its workplace cultures, it reads that much worse.

Yes, Sunset Overdrive and The Good Life were made under completely different contexts, but it’s still disappointing to see the exact same shortcomings crop up seven years on. One of the great benefits of industry is that creators are able to learn from each other, honing their products and their skills by observing the successes or failures of their competitors. And there are shining examples of coherent self-awareness in video games; Doki Doki Literature Club springs immediately to mind with its total collapse of the fourth wall. More moderately, the Metal Gear Solid series has long flirted with self-awareness, from Psycho Mantis’s mind games to the narrative fake-outs of Sons of Liberty and The Phantom Pain, which is one of the features that makes the series so memorable.

And there’s a rich vein for inspiration beyond games too. Al Ewing’s The Fictional Man plays with style and form in conjunction with its narrative to explore how stories are warped and redefined in their retellings. Stephen King’s The Dark Tower series plays with the limits of fiction with its implication that King’s entire oeuvre – and the real world – all exist within an interconnected multiverse. Inception invites us to question our reality through its closing scene. Philip K. Dick’s The Man in the High Castle emphasizes the fragility of history and questions the source of fiction through its conceit of a book that tells real-world history within a fictional setting. And Amazon’s adaptation of that work offers a subtle wink to readers by adapting that fictional book, The Grasshopper Lies Heavy, into a film.

Maybe these latter self-referential works feel better simply because they have a more serious bent than The Good Life or Sunset Overdrive. I dare say it’s more than that, though. It’s about respect for the audience. Rather than treating us as co-conspirators on a self-deprecating joke, they challenge us to view them as stories and works simultaneously. They center self-awareness as a lens to think about the place of the text within the wider world. They don’t just lean on vapid humor as a crutch – they treat us as if we can read between the lines, which ensures they’re remembered for what makes them good rather than laughable.

Published: Nov 21, 2021 11:00 am