As a long-delayed sequel to a beloved franchise, The Matrix Resurrections is preoccupied with one single question: why?

Early in the film, game designer Thomas Anderson (Keanu Reeves) is summoned into a meeting with his business partner, Smith (Jonathan Groff). The pair run a company called Deus Machina, which experienced incredible success with a video game called The Matrix and its two sequels. Anderson’s latest project, Binaries, isn’t going to plan. It is already over budget, and Anderson seems stuck in a creative rut. Smith sees an opportunity.

“Things have changed,” Smith tells Anderson. “The market’s tough. I’m sure you can understand why our beloved parent company, Warner Bros., has decided to make a sequel to the trilogy.” He continues, “They informed me they’re gonna do it with or without us.” Anderson is taken aback. The Matrix was finished. Its creation drove him to the point of a nervous breakdown, but it is a complete work. “I thought they couldn’t do that,” Anderson protests. Smith replies, “Oh, they can.”

It’s a delightfully self-aware moment that seems to offer one rather craven and cynical reason for The Matrix Resurrections to exist: because the market and the shareholders demand it. This feels like something of a confession from director and co-writer Lana Wachowski, who casts Anderson as something of an analogue (or Lanalogue, if you will) here. After all, before The Matrix Resurrections emerged, there were reports that Warner Bros. was thinking about rebooting with writer Zak Penn.

A fourth Matrix movie was something of an inevitability, particularly in an era where Hollywood will leave no established intellectual property lying fallow when it could be generating revenue. This is why cinema has come to be dominated by bold nostalgia plays like Star Wars: The Rise of Skywalker or Space Jam: A New Legacy. The Matrix is perfect fodder for that sort of shameless cash-in. It has a distinct aesthetic. The kids who grew up with it are now nostalgic adults with disposable income.

It’s easy to understand why this would horrify Wachowski. The Matrix trilogy was a labor of love for Lana and her sister Lilly. They were personal. When Anderson is asked about the protagonist of his game, he confesses, “There is a lot of me in him. Maybe too much.” There are many autobiographical echoes of Lana to be found in Anderson. To pick one example, her account of suicidal ideation on a Chicago subway platform recalls several key sequences in the Matrix movies.

The Wachowskis have always been obsessed with the creative process as something sacred and sincere. They followed the Matrix trilogy with Speed Racer, which is a movie about a kid who finds self-expression through racing. “I go to the races to watch you make art,” Mom Racer (Susan Sarandon) tells her son Speed (Emile Hirsch). “And it’s beautiful, and inspiring, and everything that art should be.” The villain of Speed Racer is the soulless capitalist system exploiting Speed’s art.

The opening act of The Matrix Resurrections is largely about spoofing the cynical absurdity of a sequel to the Matrix, in various forms and permutations. An early shot in the opening sequence pans down a neon sign for the “Heart of the City,” but the “E” is broken. From the start it’s all about the (he)art. In those opening scenes, Bugs (Jessica Henwick) finds herself a nostalgic spectator to a recreation of the iconic opening sequence of the original Matrix film, almost perfectly recreated.

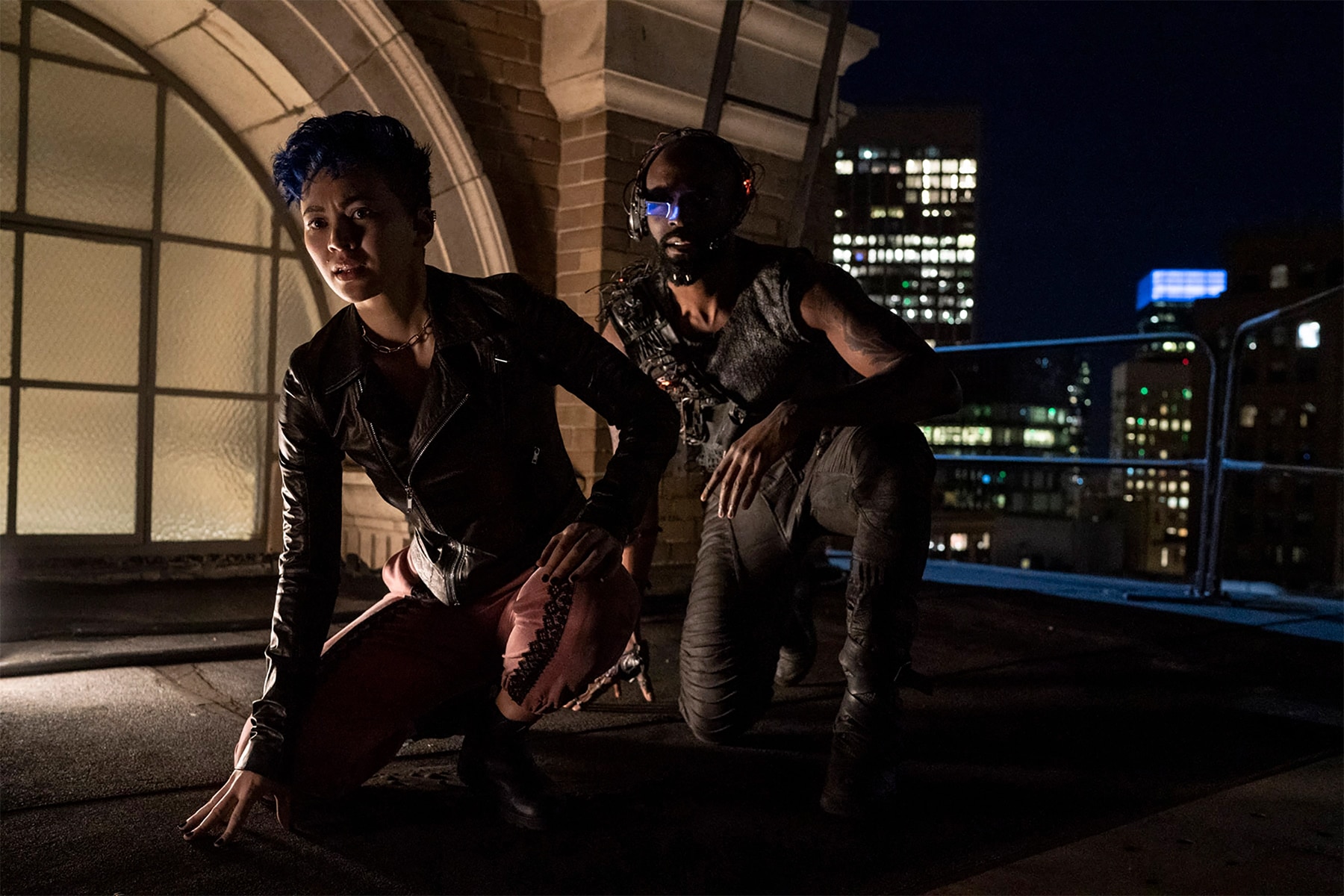

“We know this story,” Bugs observes. “So deja vu and yet it’s obviously all wrong.” Her partner Seq (Toby Onwumere) wonders, “Why use old code to mirror something new?” Seq repeatedly warns Bugs that this nostalgia is “a trap,” an observation that proves increasingly true as the film goes on. The computer program Morpheus (Yahya Abdul-Mateen II) is trapped within this opening nostalgia bait. He explains, “We can’t see it, but we’re all trapped inside these strange, repeating loops.”

Anderson coded this loop of the opening of The Matrix as an experiment, trying to create something new from something old. That’s largely what Resurrections is trying to do as a film. Much of the opening act is given over to debates about what “Matrix 4 – and who knows how many more?” – should look like. Writer Astra (Freema Agyeman) protests, “This cannot be another reboot, retread, regurgitated…” Her colleague Scott (Andrew Rothney) cuts her off, “Why not? Reboots sell.”

Within The Matrix Resurrections, multiple characters offer various justifications for this sort of franchise revival. Mirroring Smith’s argument about how “the market’s tough” and nostalgia will keep things afloat, the Machine City has been running low on power. A cynical program known as the Analyst (Neil Patrick Harris) hatched a scheme to keep everything afloat. The Analyst has brought both Neo and Trinity (Carrie-Anne Moss) back to life. He effectively pitched a reboot to help an ailing economy.

“First, I had to convince the suits to let me rebuild the two of you,” the Analyst explains. “Resurrecting you both was crazy expensive.” He resets Neo back to where he was at the start of The Matrix, a normal person oblivious to the world in which he exists. He keeps both Neo and Trinity separated, drawing power from the tension of a union that will never happen because it would mean the end of the story. “Just give the people what they want, right?” he argues.

The Matrix Resurrections is saturated with treadmill imagery. Seq describes Neo’s recreation of the opening of The Matrix as “a treadmill.” The montage of developing Matrix 4 is cut against Neo running on a treadmill, expending energy while stuck in place, running fast to get nowhere. Bugs describes the Analyst’s trap as “a treadmill.” It’s the illusion of movement, the illusion of change, and the illusion of progress.

Resurrections’ biggest fear is that the Analyst is right, that this stasis is all that audiences want. In the movie’s final scene, he is confronted by a revived Neo and Trinity. He doesn’t seem especially concerned. Speaking of the people that Neo and Trinity have vowed to reach, the Analyst insists that audiences will reject anything that departs from what they know, “They crave the comfort of certainty. And that means you two, back in your pods, unconscious and alone, just like them.”

The genius of Resurrections lies in the film’s use of nostalgia. It understands nostalgia is not an end, but a means. Bugs and Morpheus struggle to awaken Neo during their first encounter, so they restage the awakening scene from the original film. “After our first contact went so badly, we thought elements from your past might help ease you into the present,” Bugs explains. Morpheus, wearing his iconic Morpheus Sunglasses, clarifies, “Nothing comforts anxiety like a little nostalgia.” Nostalgia must be in service of something.

Lana Wachowski has talked about how the idea for The Matrix Resurrections was intensely personal, coming to her following the death of her parents. Her sister Lilly has confirmed that this was a project that mattered specifically to Lana. The Matrix Resurrections occasionally feels like an attempt to protect The Matrix from the ravages of capitalism. “They took your story, something that meant so much to people like me, and turned it into something trivial,” Bugs tells Neo.

This is the trap. When Neo tries to rescue Trinity, the Analyst traps him in a facsimile of “bullet time,” the innovative filming technique that helped make The Matrix so iconic. “I know,” he laughs. “Kind of ironic, using the power that defined you to control you.” The Wachowskis made The Matrix, but they don’t entirely own it. Studios can exploit it. Part of the genius of The Matrix Resurrections is that Wachowski doubles back on this – realizing that she can also exploit this relationship.

In the movie’s final scene, Neo and Trinity confront the Analyst. They plan to remake the world. “Before we got started, we decided to stop by to say thank you,” Trinity tells him. “You gave us something we never thought we could have.” The Analyst responds, “And what is that?” Trinity answers, “Another chance.” It feels like a fox announcing that it has been let loose in a henhouse, Wachowski thanking Warner Bros. for giving her a sizable budget and a chance to reclaim her work.

This is most obvious in the way that Resurrections re-centers the Matrix franchise as a metaphor for the trans experience, something that Lilly has stated was “the original intention.” Image and self-image are key themes. The characters no longer travel through phones, but through mirrors. The movie repeatedly draws distinctions between the image that characters project and their authentic selves in need of expression. Neo and Trinity live in bodies that are not their own.

On a more basic level, Resurrections is reflective. Notably, the film feels like a considered response to the original trilogy’s treatment of Trinity. Although Trinity was a fantastic character, she was often sidelined to focus on Neo’s arc. This marginalization of female characters is a trope so common that critic Tasha Robinson christened it “Trinity Syndrome.” Resurrections feels like a long overdue correction, Wachowski taking the opportunity to literally let Trinity soar.

However, it’s more than that. The Matrix Resurrections is the work of a filmmaker who has grown and changed in fundamental ways since the original films. Resurrections is relatively uninterested in trying to recreate who Lana Wachowski was when she made the original trilogy. With its bright colors and goofy sincerity, this could only be the work of a filmmaker who made films like Speed Racer and Cloud Atlas in the interim.

The film’s style has evolved with Wachowski. “She was explaining to us how, in her earlier work, she would storyboard things like they were comic books almost, and create exact frames of what she wanted as her way of literally controlling her narrative, because there was so much out of control inside of her,” explains actor Jonathan Groff. “Then when she embraced her identity, this articulated itself in her work and opened her up to the idea of capturing the things that can’t be controlled.”

So the film’s visual language reflects how Wachowski herself has refused to stay static. This is most obvious in the aspects of Resurrections that contrast with the earlier films: the decision to shift to handheld RED cameras, the choice to avoid overly storyboarding action sequences, the push towards a more saturated color palette. The result is a movie that doesn’t wallow in nostalgia for its own sake, but uses familiar iconography to say something interesting in conversation with past works.

In The Matrix Reloaded, the Merovingian (Lambert Wilson) complains that people are all slaves to causality. “Our only hope, our only peace is to understand it, to understand the ‘why,’” he explains. “‘Why’ is what separates us from them, you from me. ‘Why’ is the only real social power; without it you are powerless.” The Matrix Resurrections is a film that understands causality has rendered its existence inevitability, and the only hope is to find a meaningful “why.”

This is what gives The Matrix Resurrections an advantage over so many legacy sequels. It finds the “why.”

Published: Dec 24, 2021 11:00 am