This discussion and review contains spoilers for Westworld season 4, episode 3, “Annees Folles.”

Given that “Annees Folles” is a particularly meta episode of Westworld, it seems fitting that this should be a particularly meta recap. Let’s start with a fundamental truth: Recapping Westworld poses its own unique challenges.

Here at The Escapist, I have been lucky enough to recap a variety of shows: Peacemaker, The Book of Boba Fett, Star Trek: Picard, Moon Knight, The Boys, and Star Trek: Strange New Worlds. Some of those shows are better than Westworld, and some of them are worse. However, none of them offer the same sort of tension that comes from covering a show like Westworld on a week-to-week basis, where it can often feel like the series is playing a long game to deliberately wrongfoot the viewer.

Five years ago, critic Noel Murray wrote about a similar set of challenges that he faced when recapping Twin Peaks: The Return. Of course, Westworld is hardly comparable to Twin Peaks. The mysteries that drive Westworld are a lot more banal and a lot more nuts-and-bolts than the profound existential queries that played out on Twin Peaks.

Still, watching and writing about Westworld often feels more active than consuming a lot of other contemporary television. It feels like playing a game with the show itself, as if trying to identify a picture before the last piece of the jigsaw falls into place. There has been a lot of criticism of so-called “mystery box” shows since the genre was popularized by Lost, and much of that criticism is justified. However, Westworld has a decidedly more playful mood than many of its contemporaries.

Showrunners Lisa Joy and Jonathan Nolan lean into this interesting dynamic with their audience. Nolan has talked about watching movies as a child and predicting the big reveals and the endings as “a game.” He even won $50 by solving the ending of The Usual Suspects five minutes into the film. When Joy and Nolan promised to reveal the entire plot of the second season before it aired to temper fan speculation, the result was an elaborate troll.

This makes writing about Westworld a challenge, particularly in real time. The show is always setting up plot twist after plot twist, ready to reveal that the audience’s assumptions were incorrect. It’s a show where the real story of the season will only snap into focus as the finale approaches. No small amount of the fun is derived from figuring out how various elements fit together — but that means understanding that they almost certainly don’t fit together as they appear to.

It is easy to understand why this approach would be frustrating to some viewers. Not everybody enjoys an elaborate game of Three-card Monte stretched out across an entire year, no matter how much showmanship the hustle has on display. For people who enjoy Westworld, part of the fun lies in watching the art of the show’s hustle, in recognizing its familiar tricks and figuring out how those now familiar moves are being employed in sequence to some greater effect.

After all, the big trick in the show’s first season — and one that many viewers correctly spotted ahead of time — was the reveal that not all of the show’s cross-cutting story threads were happening simultaneously, but that some plot beats and character arcs were being presented out of sequence. Since that reveal, multiple timelines have just become part of the show’s narrative bread and butter, to the point that it is scarcely worth even mentioning.

In “Well Enough Alone,” William’s (Ed Harris) manipulations to reopen his new theme park are crosscut with Caleb (Aaron Paul) and Maeve (Thandiwe Newton) journeying to that theme park. One plot thread unfolds over months and presumably years, while the other takes place over a few days. The show knows that the audience understands this is how it tells its stories. The viewer understands the logic that underpins all this, and the show knows that the audience knows.

To be honest, it would be a bigger surprise for the show to reveal later in the season that Christina (Evan Rachel Wood) and Bernard’s (Jeffrey Wright) story threads were happening simultaneously with Caleb and Maeve’s adventures, rather than dislocated backwards or forwards in time. As with the show’s tendency to accelerate its storytelling in its third and fourth season, there is a sense of playfulness in the obviousness of these setups.

The fourth season of Westworld is certainly having fun as it leans into the pulpier aspects of its storytelling. There is something inherently charming about watching 71-year-old Ed Harris reinvented as an unlikely action star. While the show was never shy in its references to classic science fiction, it layers on the references here. Bernard’s dream suggests the white unicorn from Blade Runner, while he meets up with futuristic rebels who look like refugees from Mad Max.

Of course, to give the show some credit, its mystery boxes don’t exist entirely for their own sake. “Annees Folles” marks the return of “the maze,” a piece of iconography strongly tied to the first season of Westworld. However, central to that season was the reveal by Robert Ford (Anthony Hopkins) that the mystery at the show’s center was not a mystery to be solved by visitors like William. It was instead an extended metaphor for the show’s central theme: the question of consciousness.

The first season’s non-linear structure was a fun game, but it was also a thematic tool that suggested the fragmented reality similar to that experienced by Dolores (Wood) or Bernard. “The first season is rooted in Dolores’ perception of reality that we only understand [in the first season finale] is nonlinear,” explained Nolan. “In the second season, with the audience’s understanding of that, we thought we could play with our cards up, showing the non-linearity of Bernard.”

This gets at another tension when it comes to writing about Westworld. It’s difficult to figure out exactly how much depth should be read into the show. Its resonance can feel more coincidental than intentional. Westworld premiered in October 2016, almost exactly a year before the crimes of Harvey Weinstein came to light. However, the show’s first season was retroactively framed by both critics and its stars (including abuse survivor Evan Rachel Wood) as a parable for the #MeToo age — a parable that is apt.

Similarly, Nolan has explicitly stated that the civil unrest and revolution depicted in the third season was actually inspired by events in Hong Kong, even if the broadcast coincided with more domestic protests. Of course, the question is whether the artist’s intention is the only prism through which a work can be interpreted, or whether such works deserve credit for tapping into more timeless anxieties that just happen to bubble through into the consciousness as they are released.

This is perhaps another level to the game that Westworld plays with its audience. “Annees Folles” leans into this, suggesting that Westworld might be as self-aware as any of the featured hosts. The episode features yet another retread of the spectacular robbery set piece from the show’s premiere, which had already been restaged to great effect in the second season. It is no wonder that Maeve complains about having to sit through “a shabby imitation” of the show’s greatest hits.

The robbery sequence in “Annees Folles” is deliberately flat, particularly compared to the similar sequences in “The Original” and “Akane No Mai.” This flatness feels like a deliberate choice, the show making a pointed comment about having to retread familiar ground and to replay the classics. However, the question hangs over the season: Does it matter if a lifeless action sequence is clever, if the result is still a lifeless action sequence? That’s for each viewer to answer for themselves.

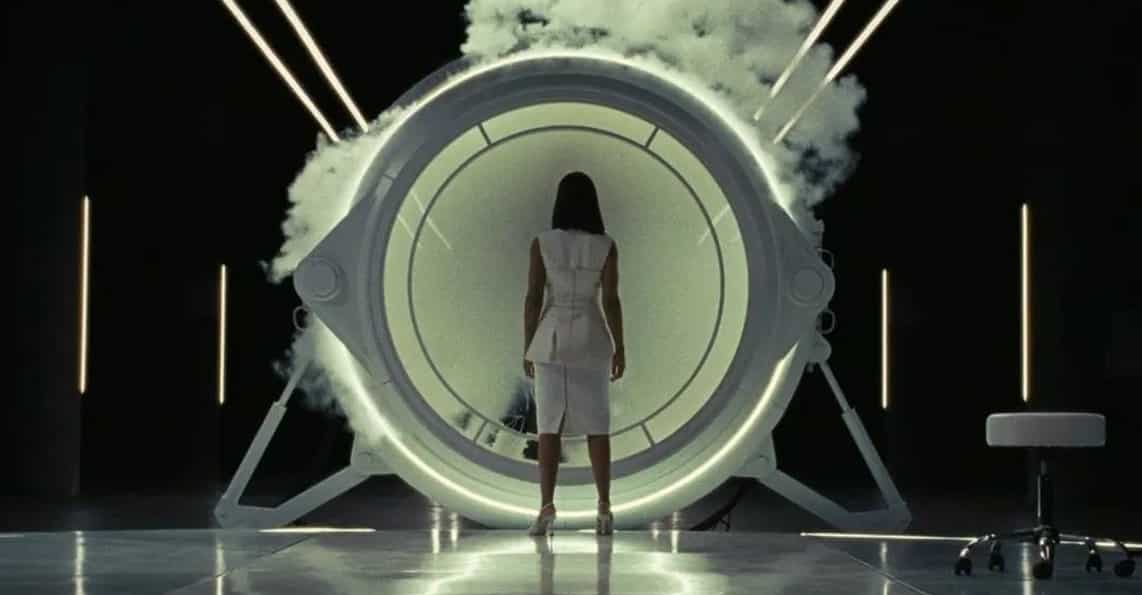

In “Annees Folles,” it is all layers within layers. Maeve and Caleb sneak into the tunnels beneath the park, but they discover that these behind-the-scenes spaces are really just an extension of the amusement park. Maeve and Caleb discover that William has folded the host revolution into the theme park as an “Easter egg,” a “hidden narrative,” or a “secret game.” Maeve warns Caleb, “None of this is real. It’s just another level of the game.”

It is all clever and an escalation of the show’s self-awareness. It also feels like a pointed commentary on the way in which capitalism appropriates and consumes everything, even the forces opposed to it. After all, The Boys might be about a massive evil corporation using superheroes to lull a population into submission, but it is still a superhero show produced by a massive (and possibly evil) corporation to sell subscriptions to its streaming service. Revolution becomes an attraction.

“This is so cathartic!” screams a wealthy white guest (Liza Weil) as she lives out her fantasy of leading a slave revolt. In some ways, it feels like a clever piece of self-criticism from Westworld, a show that has been accused of coopting the iconography of slavery and revolution from a position of privilege. For a moment, Maeve and Caleb seem to peer behind the curtain at Westworld, with Maeve hearing the hum of a machine that sounds suspiciously like Ramin Djawadi’s synth score.

Indeed, the fake-out with Frankie (Celeste Clark) seems like the show acknowledging criticisms of its portrayal of minority characters — especially children — who have suffered disproportionately in earlier seasons. Instead of using the suffering of a child to torment an adult, “Annees Folles” has both Uwade (Nozipho Mclean) and Frankie escape, while Caleb is made to suffer. It feels like Westworld deliberately engaging with its own complicated baggage.

Then again, this may be reading too much into Westworld in general and “Annees Folles” in particular. However, trying to figure out whether that is the case is part of the fun of Westworld.

Published: Jul 10, 2022 10:00 pm