With major releases like The Lord of the Rings: The Rings of Power and The Witcher: Blood Origin, this year has seen the resurrection of an old debate about the nature of adaptation. What changes are acceptable in adapting a work from one medium to another? How faithful must an adaptation be to the source material in order to be considered “true” or “great”? It is a debate that has become increasingly charged in recent decades, as more pop culture is drawn from existing properties.

These arguments about textual fidelity are very common. They allow the person making them to position their criticism as an argument from authority. After all, it isn’t simply that the person in question doesn’t like a given narrative or character choice; it is that the choice itself is wrong. Indeed, it’s possible to frame the debate in overtly emotional terms: The change is a betrayal of the source material. It is proof that the people making the adaptation don’t care about the work itself.

It’s a very comforting approach to criticism, and it even has that whiff of “objectivity” about it that appeals to people who argue about media online. A difference between one version of a story and an adaptation of that story isn’t a matter of taste — it is an objectively verifiable fact. The unspoken assumption that the difference must be bad is a matter of taste, but that often sneaks by into the subtext of the argument. It saves the hassle of actually engaging in discussion.

The Witcher: Blood Origin is bad. It also makes fairly substantive deviations from the established lore. These deviations themselves might be bad, but they are not bad because they are deviations. They are bad because they are poorly written, poorly judged, and occur in a narrative that was weak enough to begin with, even before it was hacked to pieces in the editing booth. The fact that Blood Origin is different from the source material is incidental. It would still be bad even if it were faithful.

However, unpacking all of that takes effort. It also involves some measure of subjectivity. There may well be people out there who greatly enjoy Blood Origin and who can make compelling arguments for their preference. Their criteria for evaluating a work may be different. The argument that it is inherently bad because it is different serves to sidestep these potential arguments. It is a trump card that can be played at any moment in time, overriding the debate.

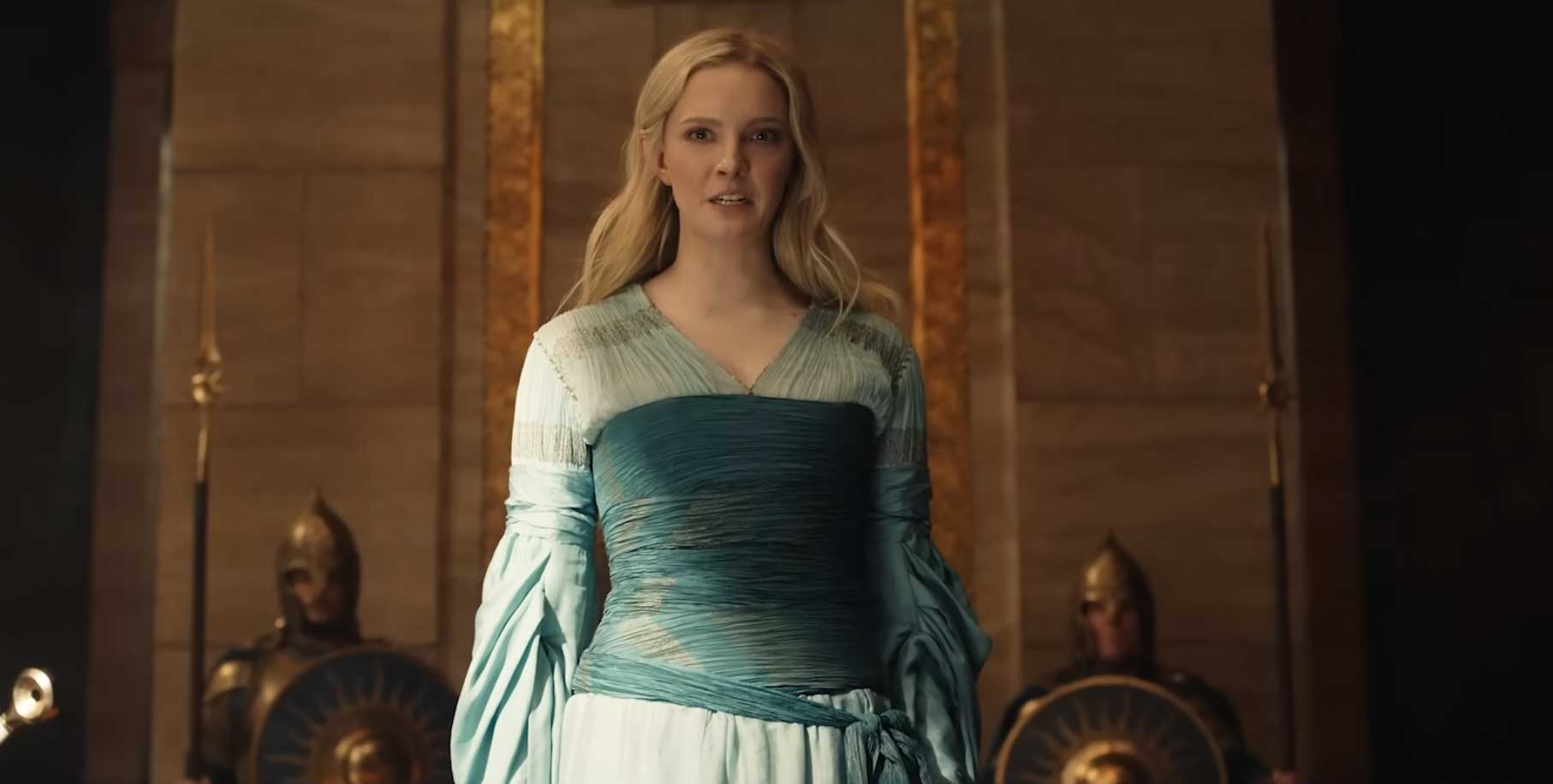

Of course, any attempt to pull back and zoom out will reveal how arbitrary this criticism can be, as well as how it is often a mask for the preferences of the person making it. The Rings of Power is a useful case study here, given the number of complaints it has generated over its supposed betrayal of the source material. In particular, there has been a vocal strain of criticism concerning the show’s treatment of Galadriel (Morfydd Clark) as something akin to an action heroine.

The Rings of Power invites comparisons to Peter Jackson’s adaptation of the Lord of the Rings trilogy. The production design evokes the movies. The decision to shoot (at least the first season) in New Zealand ensured some continuity. Jackson’s composer Howard Shore wrote the title theme, and series composer Bear McCreary has talked about wanting “to honor the legacy of what Howard Shore created.” There were even early talks about Jackson himself being involved with the show.

There is some suggestion that the Tolkien estate vetoed Jackson’s involvement with the series. If so, it seems that their long-stated distaste for his adaptations may have been a factor. Christopher Tolkien claimed that Jackson had “eviscerated the book by making it an action movie for young people aged 15 to 25.” If Jackson’s film adaptations weren’t faithful enough to impress the son of J.R.R. Tolkien, then perhaps fidelity isn’t the ultimate arbiter of a work’s quality.

Christopher Tolkien was not alone in accusing Jackson of altering the source material for the worse. “Look, I understand that movies are not books, that the pace requirements are different, and that what’s suspenseful on the page may not be suspenseful on the screen,” acknowledged Kate Nepveu at Tor.com. “But was it really necessary to create suspense through making so many characters self-centered, short-sighted, and ill-informed? By, in other words, diminishing them?”

There remains a tension within The Lord of the Rings fandom between book fans and film fans. In many cases, the changes that book fans hate are the choices that film fans love. Most obviously, some book fans are vocal in their objections to the changes that Jackson made to Faramir (David Wenham) in The Two Towers, even labeling him “Far-from-the-book-Amir.” However, film fans consider Faramir to be one of the most compelling members of the franchise’s ensemble.

Indeed, some of the criticisms of The Rings of Power have very specific echoes in early objections to Jackson’s The Lord of the Rings. Book purists were “furious” that Jackson had expanded the role of Arwen (Liv Tyler) to involve a horse chase in The Fellowship of the Rings. There were criticisms that Arwen had been “turned into an action heroine.” In some ways, the fan reaction to the Lord of the Rings trilogy foreshadowed so much of what pop culture would become.

As others have noted, there was a sense that Jackson and his collaborators were “nearing the end of their polite tolerance of the meddlesome, scolding side of Tolkien fandom” by the time that they were working on The Two Towers. History appears to have vindicated the production team. Regardless of the changes that they made to the source material, the Lord of the Rings trilogy remains a singular accomplishment. It was The Lord of the Rings as only Jackson could have made it.

There are more extreme examples of the liberties talented creators can take with source material. In 2006, Michael Mann reimagined Miami Vice for the 21st century. Although it was an extremely loose adaptation of the episode “Smuggler’s Blues,” itself an adaptation of a Glenn Frey song, it cast aside much of the iconic look and texture of the classic series. Very little of the movie even took place in Miami. The movie was divisive when released, but has been reclaimed as a masterpiece.

When Phil Lord and Christopher Miller made a 2012 cinematic adaptation of the 1980s television show 21 Jump Street, they reframed the high-concept police procedural as a self-aware spoof. Although the show had been successful enough to be the first hit on the young Fox Network, there was minimal outrage over it. Lord and Miller’s adaptation was a comic highlight of the 2010s and a movie successful enough to spawn an even more self-aware sequel in 22 Jump Street.

Again, there is no one-size-fits-all approach to adaptation. When Dax Shepard adopted a similarly irreverent approach to his big-screen take on 1970s motorcycle cop show CHiPs back in 2017, the results were catastrophic. However, CHiPs wasn’t bad because Shepard hadn’t shown suitable reverence to the source material, any more than 21 Jump Street was good because Lord and Miller had embraced irreverence. CHiPs was simply a bad movie, unfunny, uninspired, and unbearable.

Faithfulness to source material is not an objective signifier of quality. If it were, Gus Van Sant’s shot-for-shot remake of Psycho would be regarded as a masterpiece for the care with which it recreates Alfred Hitchcock’s original. Instead, the movie was a critical and commercial flop. Van Sant’s Psycho is perhaps most interesting as a piece of experimental art, and it is perhaps best experienced as Steven Soderbergh’s mash-up of the two films as Psychos.

In some ways, Van Sant’s Psycho is a quietly influential film. Its legacy lives on in these debates that praise faithfulness as an unambiguous virtue, but more directly in the slate of Disney’s “live-action” adaptations of its classic cartoons, like The Lion King or Aladdin, which are often slavish in everything from soundtrack to dialogue to shot composition. There is no acknowledgement of the differences between animation and live action — or effects emulating live action.

Adaptation is an art form like any other. Film, television, books, and video games are all different forms of media. They all work in different ways. What works in one will not necessarily work in the other, and there is no objective metric to measure the quality of an adaptation in one form to its source material in another. In many cases, the quality of the adaptation is largely independent of the quality of the object that inspired it.

The Rings of Power and Blood Origin are both shows with fairly significant problems. Copying and pasting lines of text directly from the source material will not fix the obsession that The Rings of Power has with mystery boxes and will not make Blood Origin’s dialogue, characterization, or editing any better. It’s a distraction from the real problems and often a way of cutting off more interesting conversations. It doesn’t matter how faithful an adaptation is, simply how good it is.

Published: Dec 29, 2022 11:00 am