This discussion of the smallfolk in House of the Dragon contains spoilers for the first six episodes of the series.

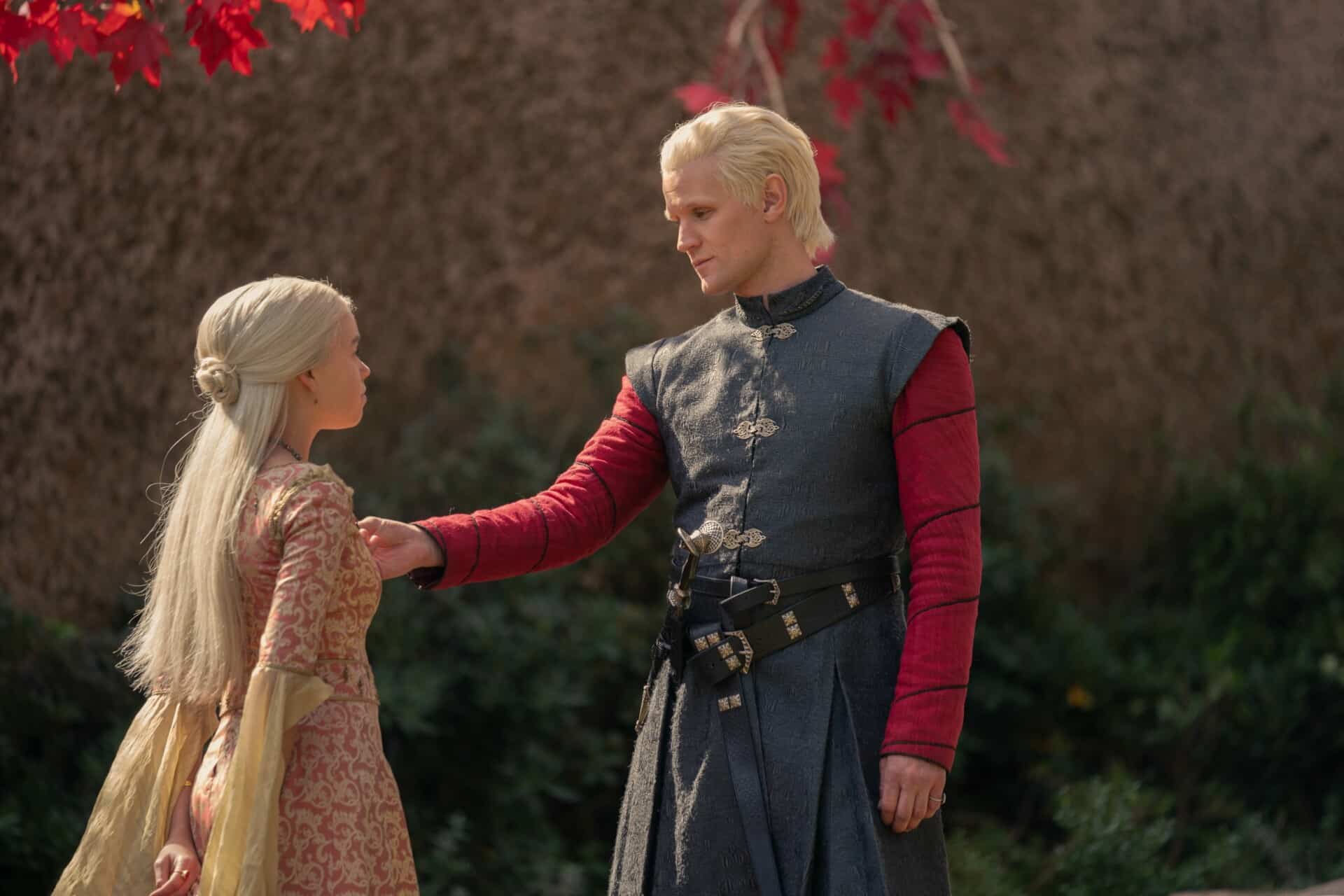

There is an interesting scene in the fourth episode of House of the Dragon. Wary of her obligations as presumed heir to the throne, Princess Rhaenyra (Milly Alcock) has sneaked out of the Red Keep into the wider city of King’s Landing. Accompanied by her uncle Prince Daemon (Matt Smith), Rhaenyra is able to enjoy a different sort of life. She is surrounded by fortune tellers and public performers, bars and brothels. It is a world very different from the one in which she usually travels.

It is also very different from the world in which House of the Dragon is set. At its core, House of the Dragon is a medieval soap opera set in an ensconced world of wealth and privilege. The majority of “Second of His Name” unfolds during a royal hunt led by King Viserys I (Paddy Considine). The bulk of “We Light the Way” is built around Rhaenyra’s royal wedding to her cousin Laenor (Theo Nate). There are lots of scenes set in dining halls and gardens, in which the realm’s rulers discuss its health and fate.

Of course, this was also the case with the series that inspired House of the Dragon, Game of Thrones. That show’s most iconic prop was the Iron Throne. It was preoccupied with other seats of power like King’s Landing, Winterfell, the Eyrie, and the Twins. The show would frequently cut between various throne rooms and was even named for the power plays of the Westerosi ruling class. There is a reason the show attracted a fandom of our world’s elite class, from Mark Zuckerberg to Elon Musk.

Still, Game of Thrones was built around the fundamental understanding that this insulated world of would-be kings and queens stood atop another world entirely. In both House of the Dragon and Game of Thrones, the ruling class refer to the peasants and commoners of Westeros as “the smallfolk.” In both shows, there is a deliberate disconnect between those who rule and those who are ruled, with the former seeing the latter as little more than cannon fodder.

Halfway through the first season of House of the Dragon, one of the biggest differences between it and Game of Thrones is the understanding of this relationship. Game of Thrones might have been focused on the ruling class, but it also regularly checked in on the lives of the ordinary people across Westeros and Bravos. At the Wall, the Night’s Watch was composed of a mix of social classes, from common criminals like Karl Tanner (Burn Gorman) to bastard royalty like Jon Snow (Kit Harington).

The sprawling narrative of Game of Thrones allowed the show to serve as something of a travelogue, using characters like Arya Stark (Maisie Williams) and Sandor Clegane (Rory McCann) to showcase the range of life experiences in this fictional world. In the fourth season, Sandor steals from a farmer (Finbar Lynch) and his daughter (Trixiebelle Harrowell), arguing that they would be dead by winter. Three seasons later, Sandor returns to the house and finds their corpses, his prediction confirmed.

Many of the characters who find themselves drawn into the epic sweep of Game of Thrones come from the peasant classes. The scheming Varys (Conleth Hill) was a former slave. The loyal Davos Seaworth (Liam Cunningham) was the son of a crabber who accumulated power as a smuggler. Even Gendry (Joe Dempsie), the bastard son of King Robert Baratheon (Mark Addy), was raised and trained as a blacksmith. The show was always conscious of this class tension.

There is a strong sense in Game of Thrones that life exists outside of the political maneuvering of the upper classes. The Brotherhood Without Banners is a ragtag band of former knights and soldiers who reject the feudal system that governs Westeros to fight anyone who would “prey on the weak.” Brother Ray (Ian McShane) is a former mercenary who builds a commune in the hills, apart from all the plotting and scheming. The High Sparrow (Jonathan Pryce) stokes the possibility of revolution.

Game of Thrones was not romantic about the peasants. “The common people pray for rain, health, and a summer that never ends,” Jorah Mormont (Iain Glen) warns Daenerys Targaryen (Emilia Clarke), who has spent her life believing that the smallfolk eagerly await her return as ruler. “They don’t care what games the high lords play.” The relationship works both ways, with Gendry scolding Davos, “We’re not really people to you, are we? Just a million different ways to get what you want.”

Daenerys fashions herself as the “breaker of chains,” but really she just sees the smallfolk as a means to the end. When she crucifies 163 slave masters of Meereen, she never considers that she will be ruling a city populated by their relatives and colleagues. She arrives in Westeros as an invader, unwelcome and uninvited. She burns Randyll (James Faulkner) and Dickon Tarly (Tom Hopper) for refusing to bend the knee to her. She talks a good game, but she is still invading royalty.

The central thesis of Game of Thrones is that “kings and queens are selfish people who will kill you when they need you to die.” The show is about what happens “when individual leaders accumulate strength that refuses to be questioned or moderated.” This is most obvious when Daenerys realizes that she will never be loved and so must rule by fear. When Daenerys rains fire on the inhabitants of King’s Landing in “The Bells,” Game of Thrones is demonstrating what it takes to win.

One of the biggest differences between Game of Thrones and House of the Dragon is that the latter seems uninterested in the affairs of the common people who will get caught in the crossfire of Rhaenyra’s pursuit of the Iron Throne. There is a telling scene in “King of the Narrow Sea,” when Rhaenyra attends a stage show mocking her ambitions to rule in favor of her younger brother Aegon II. Dressed in peasant cosplay like Jasmine (Linda Larkin) sneaking into the market in Aladdin, Rhaenyra jeers at it.

“Jest if you will, but many of the smallfolk are likely to believe that, as a male, Aegon should be the heir,” Daemon explains. His niece is unconcerned. “Their wants are of no consequence,” she states. Daemon counters, “They’re of great consequence if you expect to rule them one day.” However, it seems that House of the Dragon has sided with Rhaenyra. Already, reviewers are boasting that they are “Team Rhaenyra,” having learned nothing from the “Team Daenerys” debacle.

Six episodes into House of the Dragon, there is a worrying sense that the show has responded to the backlash over Daenerys’ turn towards the end of Game of Thrones by stripping out a lot of the moral complexity around this world of royalty. While the show’s much narrower focus on the ruling class helps keep the show’s narrative under control, it also makes these characters less complex by limiting the lenses through which they might be viewed.

It’s worth comparing that scene in which Rhaenyra watches the play dramatizing the continent’s royalty to a similar plot beat in Game of Thrones. The sixth season of Game of Thrones devotes an entire subplot to a Braavosi dramatic troupe led by Izembaro, played by Oscar-winning actor Richard E. Grant, as they dramatize events from earlier seasons. It’s a clear contrast in approaches. The players in Game of Thrones were characters. The actors in House of the Dragon are just props.

To be fair, there is some sense of self-awareness here. The opening scene of “Second of His Name” opens with an anonymous Velaryon knight (Aron von Andrian) being tortured by the Crabfeeder (Daniel Scott-Smith). As he is about to die, Daemon appears riding his dragon Craxes. The knight praises his savior, shouting desperately to be heard over the din of battle. However, the sequence has a blackly comic conclusion, as the anonymous knight is casually crushed beneath Craxes’ claw.

The tight focus of House of the Dragon recalls the insulated world of HBO’s Succession. Both are stories about competing heirs to a kingdom overseen by a ruler in his twilight. “Second of His Name” has its own variation of Logan Roy’s (Brian Cox) “boar on the floor.” Viserys’ hunting trip recalls an opulent Roy family retreat. “The Princess and the Queen” even has Aegon II (Tom Glynn-Carney) masturbating at his window overlooking King’s Landing, recalling a similar sequence with Roman Roy (Kieran Culkin).

Charitably, one might argue that, like in Succession, the insulated worldview of House of the Dragon offers a pointed commentary on how the upper social classes exist entirely removed from the world that they seem to rule. However, Succession is notable for being one of the rare depictions of absurd wealth in television that manages to completely avoid glamorizing it. Succession makes wealth look pathetic and claustrophobic. In contrast, House of Dragon makes ruling look pretty fun.

The very insightful Lee Murkey recently noted that a lot of modern pop culture has begun leaning into a “top down observation of power,” which can erase everything except the power fantasy of ruling. There is a lot to like about House of the Dragon, but it really feels like the show could do well to get an outside perspective on its eponymous power players.

Published: Sep 26, 2022 11:00 am