PlayStation VR gave me two gifts. The first was an astonishingly vivid waking experience of my longest-running recurring nightmare. Playing Kowloon’s Gate VR, an adaptation of the 1997 lo-fi surrealist adventure game for the original PlayStation, trapped me inside the same hazy halls of my absolute worst nights. The primitive polygons and warped human faces of the weirdos wandering around its hellish version of the Walled City are straight out of the rotting wooden cabin of my dreams. Kowloon’s Gate left me with the same phantasmagorical lack of bodily control — most VR games do — and forced me past the same wrought iron doors that won’t open. It’s a good thing you have to actually remove the helmet entirely to save the game and examine the “psychological pictures” (just snapshots of specific spots in the environment) that let you progress through Kowloon’s Gate. It’s like the goddamn thing knew where it was taking me and that I’d need a break.

There’s a little bit of nightmare in every VR game, though, and the second gift comes from that omnipresent fear. Wipeout Omega Collection puts me in the cockpit of a Feisar racing ship, its baby blue aluminum chassis glimmering just beyond my peripheral vision like I always wanted it to. But my hands are locked endlessly in place when I look down, creating not so much a phantom pain as an indistinct numbness as I gawp at the futuristic landscape speeding by. Batman: Arkham VR gives me my very own Batcave and locks my feet in place. Even as Tetris Effect envelopes me in warm wash of heavenly beats I lose the firm connection I have to the world I’m actually sitting in. The rhythmic ecstasy of music fades because in VR I cease to be a sensual being. The second gift VR gave me is the opposite of ego death.

Depending on your idea of what constitutes a good time, that experience could either be existentially harrowing or god damn awesome. Explained in Jungian psychology and Joseph Campbell’s The Hero With a Thousand Faces, ego death is the dissolution of your sense of self. Rather than feeling like an independent body thinking individual thoughts, you have an all-encompassing feeling of oneness with everything possible and not possible. It’s hard to talk about ego death and not sound like a complete dink.

Kowloon’s Gate

Put aside the airy inadequacy of language to capture ego death, though, and you might recognize a feeling you’ve had playing hypnotic or demanding video games. It’s the “zone” a high-level Call of Duty player might describe, that feeling that falls on your brain when you’ve been playing Tetris on endless for a whole day straight and you can’t stop picturing the tetriminos tumbling and rotating in your mind’s eye. Video games can engender a powerful feeling that might not be ego death precisely, but lives in the same place, breaking down the barriers that stand between you and everything not you.

Virtual reality seems like a potentially wider threshold to that feeling, something that could more readily and powerfully bring you into the zone. It delivers total sensory immersion in an imaginary world through a headset, headphones and motion controllers with haptic feedback. With that PlayStation VR bobbing on my dome, Kowloon’s Gate’s vision of my very own nightmares should be pumped and primed to knock down the walls of my psyche and rebuild me into some Snowcrash version of Campbell’s eternal hero. But it doesn’t.

In isolating your body but simultaneously trying to simulate your body’s natural state — natural head movements are echoed in the game world, but your actual head is still trapped inside what amounts to an ergonomically considerate box cutting you off from the world — VR puts you in a place where everything reminds you of your body’s limitations. Every time I see some disembodied ping pong paddle waving around in front of me mimicking my real hand movements, every time I see a mech pilot’s legs locked in place in a cockpit I can freely look around, the effect is the same. All I can think about is how, in this virtual world, the only thing that actually exists is me. My body is trapped, but my ego feels immortal, immoveable.

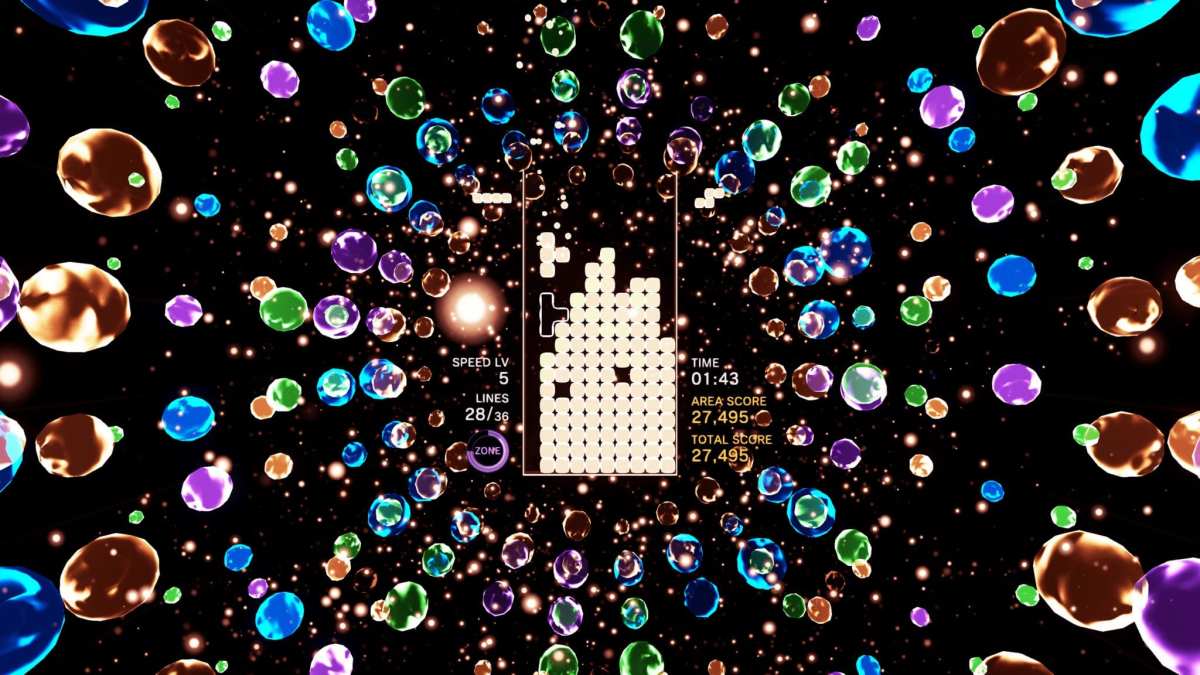

Tetris Effect exemplifies this anti-ego death feeling better than most games since VR-free Tetris is so effective at evoking the inverse. Tetsuya Mizuguchi’s (Rez, Lumines) take on the puzzle game standard is a sensory feast. Slide the visor down and clamp on the noise-cancelling headphones, and you’re adrift in a sea of impressionistic fireworks, swelling melody, and coaxing feedback that comes both from clearing lines successfully and the throbbing pulse of the controller’s vibrations. When you’re watching a desert caravan made of light points morph into an astronaut doing donuts on the moon and dropping those precious long blocks for a perfect tetris as some ecstatic techno song crests, the game can be overwhelming. But the whole thing is as confining as a good dream, so personal no one will ever get why it felt that way. Even someone following a PSVR game on the screen isn’t really seeing and hearing what you are. The VR game is, inexorably, just for you.

And I don’t hate VR for this. Unlike actual ego death, it can be profoundly entertaining and even thought provoking. My experience of ego death on psilocybin mushrooms left me exhausted and kind of bored. There was no boundary between me and all matter in space time and life was the best it could possibly be but simultaneously the worst. It was transcendent but totally mundane. Honestly, I just wanted to go to bed. That tree outside is me, I’m the tree, enough, I get it, ugh. Playing VR games, on the other hand, can be exhausting after a while because of how enervating they can be. But they’re never boring.

Social VR games like Star Trek: Bridge Crew gain a new dimension they wouldn’t have as a tabletop or screen-based game since you’re forced to bodily inhabit the world. You’re really there on the ship. You’re stuck, but you’re there. Satires like The American Dream, which attempts to exaggerate the use of guns in suburban America to an absurd degree, can treat their subjects as both abstract and guttural in way that you couldn’t without VR. The game may not be great, but using technology to replace my hands with guns is a powerful way to make an argument.

The American Dream

Even classic game genres can gain new depth in VR. Astro Bot Rescue Mission takes the old run and jump fundamentals of Super Mario Bros. and makes the relationship between character and player more explicit. The VR helmet turns you into a literal nanny for the adorable cartoon scamp you’re making collect coins and stomp on squishy robots, and it made each failure in the game more fraught than if you’d just missed another tricky jump before walking away from the TV for a break. It also made each finished stage and every secret discovered more edifying since it feels like you’ve done something personally rather than accomplishing something on behalf of an imaginary character.

I’ve had a great time in VR games. I love that video games can deliver the experience of bungie jumping into impossible spaces with my hands tied behind my back by real life sci-fi technology, even if the result is as discomfiting. But as enriching as VR games’ gifts can be, they all feel empty. Video games illuminate the real world and our relationships in it, a mirror that can show us things not readily seen. Every VR game comes with an ineludible detachment from the world because of the way the technology inherently works. No matter how free you are to explore, you have to cover your eyes in plastic and padding and heat. You have to surround your ears with buds or plush padding. Your hands have to curl around the controller. You’re secure in those games, but you’re also alone, an inevitable body in space.

Published: Jan 11, 2019 04:41 pm